Center for People Empowerment in Governance (CenPEG)

07 May 2024

Two Years of the Marcos Presidency:

Political and Governance Trends

As the Marcos presidency ends its second year in office and starts its mid-term cycle, the main political and governance trends in its line of march show greater clarity. Driven by a preoccupation with changing the public narrative about the harsh and corrupt rule of his father’s dictatorship (1972-1986), President Marcos engages in a selective rebranding of past rites and practices while avoiding the blatant excesses of the two administrations he is most linked with (Marcos, Sr. and Duterte).

However, barely two years into his term of office, President Marcos confronts a local and global environment that seethes with the dead weight of the past and the uncertainties and volatility of the present. At least two of these urgent concerns will heavily impact the remaining years of his presidency: the heightening conflict between the Marcos and Duterte political clans and the unresolved conflict with China over the South China Sea/West Philippine Sea.

Political Restoration and the Marcos Dynastic Legacy

With a winning majority of 58 percent of the votes cast in the 2022 presidential election, President Marcos presents a strong anchor for his claim that the public has vindicated the restoration of the family dynasty. The election results continue to be challenged by civil society election watchdogs as a manipulated result of the country’s automated election system. However, this contested presidential victory was also made possible by the alliance of the country’s most powerful political clans and the weakness of the fragmented political opposition. This electoral victory immediately translated into a supermajority in Congress. In the House of Representatives, a Marcos cousin, Rep. Martin Romualdez assumed the House Speakership, and the president’s eldest son, neophyte Rep. Ferdinand Alexander “Sandro” A. Marcos, was anointed as a senior deputy speaker.

In his first two years in office, President Marcos has sought to navigate the highly divisive and contentious political legacies of his late father and that of former President Duterte. While his father’s record of plunder and human rights abuses is now well-documented, the incumbent president has used significant resources and political capital to craft a different narrative about the years of dictatorship. Indeed, to a new public with little or no direct memories of this contentious past, that critical conjuncture can be reinterpreted and reappropriated through a different narrative and adroit use of power.

President Marcos’ relationship with former president Duterte and his larger clan is more difficult because the political context is a continuing past marked by consequential power plays and political realignments for dominance. For instance, former president Rodrigo R. Duterte never endorsed the candidacy of Marcos even while his daughter, Sara Duterte, former Mayor of Davao City, ran as Marcos’ winning vice-presidential candidate. Birthed by an opportunistic alliance, the Marcos-Sara Duterte team showed signs of unraveling from the first year of the administration. With the two most powerful and ambitious political clans well-positioned to contest positions of power, it is not surprising that a collision course is now unfolding.

Preserving Dynastic Interests and Family Rebranding

Winning the country’s highest executive position has provided President Marcos a most enviable position to address the family’s material and financial interests long besieged by various legal cases filed locally and abroad since the fall of the dictatorship in 1986.

The legendary wealth of the Marcoses continues to be surrounded by controversy involving hidden and ill-gotten resources, murky offshore transactions and deposits, ostentatious spending by family members, and unending litigations about ownership of resources here and abroad between the government, the family, and its cronies. Suggestive of the magnitude of these resources in question was the P170 billion pesos already recovered by the Philippine Commission on Good Government (PCGG) despite the acknowledged lack of support by various administrations of such efforts.

Among the well-known decided cases involving the ill-gotten wealth of the Marcoses was the Supreme Court decision in 2003 ordering the return of more than US$658 million from their Swiss bank account to the Philippine government; in 2012, the forfeiture of assets, properties, and funds by Arelma, Inc., a Marcos dummy corporation; in 2017, a Supreme Court ruling affirming an earlier Sandiganbayan (anti-graft court) judgment forfeiting Imelda Marcos’ ill-gotten pieces of jewelry known as the “Malacañang Collection.” Imelda Marcos, the former first lady, was found guilty in seven criminal cases and sentenced to prison time of 42 to 72 years in 2018 but she never served this conviction.

As late as 2023, the Sandiganbayan continued to adjudicate and rule on wealth cases involving the Marcoses and their cronies. In three cases, the Sandiganbayan ruled in favor of the Marcoses and their cronies. These civil forfeiture cases filed against them by the PCGG and dismissed by the Sandiganbayan in 2023 included Civil Case No. 14-1987, Civil Case No. 0024-1987, and Civil Case No. 0167-1996. The 1987 case (No. 14) involved almost P600 million in assets that the government sought to recover from the Marcos family and its cronies while the other case filed in the same year (Case No. 0024) involved millions of loans from state-run financial institutions allegedly secured through the dummy corporations of the ruling family. Civil Case No. 0167 filed in 1996 focused on recovering 42 parcels of land “unlawfully acquired” during the martial law period by Alfredo Romualdez, brother of Imelda Marcos, and his corporate co-defendants. However, in 2023 the Sandiganbayan rejected a petition by Imelda Marcos and her daughter Irene to recover the properties sequestered from them in a P200 billion civil forfeiture case dismissed earlier. This failed recovery plea involved a frozen trust account of P50 million and several sequestered companies and properties.

The presidential incumbency of Marcos and his full embrace of American global strategic interests have also enabled his family to sidetrack a celebrated human rights class suit filed in the United States. In a contempt judgment signed by Judge Manuel Real, the District Court of Hawaii awarded US353 million in 2011 in favor of the Filipino human rights victims and specifically named Marcos, Jr., and Imelda Marcos as representatives of the late dictator. This decision was affirmed by the US Court of Appeals in 2012 and a new judge, Derrick Watson, extended the judgment on contempt to January 2031.

Finally, the presidential victory of Marcos in 2022 has also sent to the back burner the unpaid tax liability of the late President Marcos and the unpaid income tax returns of Marcos, Jr., from 1982-1985. In 1991, the Bureau of Internal Revenue issued a deficiency estate tax assessment of over P23 billion against the heirs which had ballooned to about P203 billion in 2022. Marcos, Jr., contested the deficiency estate tax assessment in 1993 but lost the case in the Court of Appeals. In 1997, the Supreme Court rejected the appeal by Marcos, Jr., and stated in the final decision that, “The course of action taken by petitioner (Marcos Jr.) reflects his disregard or even repugnance of the established institutions for governance in the scheme of a well-ordered society.”

In his first two years in office, Marcos appropriated convenient symbolic rites and practices from his father while maintaining a calculated distancing from the excesses of former President Duterte’s authoritarian leadership. Reminiscent of the official slogan and theme of his father’s “Bagong Lipunan” (New Society) during the years of dictatorship, the new president has launched a similar branding and communications strategy with his “Bagong Pilipinas” (New Philippines) narrative. Using this rallying slogan, Marcos called for “deep fundamental transformations in all sectors of society and government . . . towards the attainment of comprehensive policy reforms and full economic recovery.”

President Marcos has re-introduced the KADIWA Program originally initiated by his father’s administration to address the high prices of food commodities at the height of the oil crisis in the 1970s. With the current administration facing a similar crisis of high food prices and inflation, President Marcos has re-established KADIWA stores to serve as distribution centers for various food items produced by farmers and fisherfolk cooperatives and community-based organizations. Subsidized by a grant from the Department of Agriculture, these KADIWA stores (permanent, pop-up, and on-wheel stores) seek to provide cheaper, subsidized food prices but estimates show that at best only about 30 percent of poor families nationwide can access these centers.

While a stopgap measure to soaring food prices, especially rice, the Kadiwa project also detracts from the more serious problems of addressing the backwardness of our agricultural sector, the control by powerful trading blocs of food pricing and marketing, and the leakage of scant fiscal resources to corruption in this project. As shown by the failed record of these projects in the past and the lack of determination to solve the continuing structural problems of our agricultural and fishing sectors, the KADIWA reincarnation appears to be another unsustainable rebranding initiative by the current president.

In another policy initiative in his first year of office that established a sovereign wealth fund called the Maharlika Investment Fund (MIF), President Marcos used the name “Maharlika” (the Nobility), an apparent reference to his father’s claim of having organized a World War II guerrilla organization with the same name. This claim by Marcos, Sr. was later debunked as fictitious by official war documents of the United States Army. Fast-tracked at a time when the country faces severe fiscal deficits, massive debts, and lacking surplus revenues from stable industries, the MIF was heavily criticized as an ill-advised and ill-timed project by independent professionals and civil society organizations. Moreover, the MIF was also launched during grave uncertainty in the global economic and geopolitical environment.

The MIF was funded by a P50 billion and P25 billion seed capitalization from the Land Bank of the Philippines and the Development Bank of the Philippines, respectively. Critics point out that these subsidies by the two major government banks undermine the capitalization of these institutions while diverting funds mandated for local farmers and development projects for sustainable manufacturing and industrialization projects.

Finally, critics further point out that the independence of the MIF’s management board is compromised with the watering down of the advanced educational degrees and proven work experience originally required of board officials even as President Marcos enjoys the final authority to appoint all board officials.

Presidential Leadership

In his first two years in office, President Marcos has pursued a muddling-through policy approach to national problems even as he reveled in his role as the country’s chief articulator of foreign policy. For his cabinet, he has assembled a mixed bag of experienced lawyers for his legal team, veteran technocrats and business magnates for his economics cluster, seasoned politicians for social, educational, and administrative services, and a security cluster bound by a strong pro-American orientation and counter-insurgency mindset.

In need of legal expertise and perhaps to strengthen his claim that “he has no impulses to authoritarianism whatsoever,” the president appointed Lucas Bersamin, the former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, as his executive secretary. In a surprise appointment, the president also inducted former Senate President Juan Ponce Enrile as his chief legal adviser. With a storied, controversial political career, Enrile served in various cabinet positions (finance, defense, Martial Law administrator, etc.) during the presidency of Marcos, Sr. and was also a lead conspirator of the military mutiny against Marcos Sr. in 1986. Against a body of well-documented evidence, Enrile asserted at one time that no human rights abuses took place during the dictatorship. Enrile was one of three senators charged by the Sandiganbayan with plunder and graft charges in 2014 concerning the unlawful use of pork barrel funds (Presidential Development Assistance Fund) linked with businesswoman Janet Lim Napoles. Interestingly, it was then Supreme Court Associate Justice Bersamin who wrote the majority decision in 2015 granting bail to Enrile for “humanitarian reasons”.

For his economics cluster, Marcos assembled a group of experienced technocrats and business billionaires to drive the ambitious Philippine Development Plan, 2023 – 2028. The PDP seeks to achieve “deep economic and social transformation to reinvigorate job creation and accelerate poverty reduction by steering the economy back to a high-growth path.” However, as shown by the country’s experience with its technocracy, even the best-trained and well-positioned among them generally succumb to powerful and partisan political pressures. The key Marcos economic technocrats failed their first major test when they supported the ill-studied, extremely risky Maharlika Investment Fund fast-tracked by the Marcos-Romualdez leadership. Moreover, the leading technocrats have also been unenthusiastic about industrial policies that usually underpin plans for “deep economic and social transformation” as dramatized by Asia's successful economic development paths.

Expanding his economic team, Marcos appointed two influential business leaders, Sabin Aboitiz of the Aboitiz Group of Companies and Frederick D. Go of the Gokongwei conglomerate. Aboitiz heads the presidential private sector advisory council which includes the country’s leading business corporate leaders, while Frederick D. Go serves as the presidential adviser on Investment and Economic Affairs. Go’s job description makes him the chair of the Economic Development Group which includes the Department of Finance, the National Economic Development Authority, the Department of Trade, the Department of Budget Management, and their attached agencies.

However, like the key economic technocrats, the business leaders are not keen on supporting industrial projects since their conglomerates have prospered mainly on less risky and high-profit, rent-seeking ventures in local real estate development, banking, retailing, and some low-end manufacturing. As conceded by a former finance secretary, the top business leaders are more interested in harvesting low-hanging fruits rather than investing in sustainable industrial projects that deploy skilled labor and provide stable and quality jobs with long-term strategic impact on the country’s economic growth and development.

Relations with Congress

In a presidential system where the electoral legitimacy and tenure of the executive and members of Congress are independent of each other, governing could be a problem when the president and the legislative members come from different parties. However, this has not been a problem in the Philippines because of the weakness of parties and the dominance of political families. This institutional reality has allowed for the convenient realignment of forces and political loyalties that favor the incumbent president because of the latter’s far greater command of resources and patronage.

In the two-chamber composition of the Philippine Congress (a House of Representatives and a Senate), Marcos commands the overwhelming support of the lower house even as he ran under an alliance that included four loosely organized parties: his party, the Partido Federal ng Pilipinas, the Hugpong ng Pagbabago of Sara Duterte, Lakas-CMD of former president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo and Martin Romualdez, and Pwersa ng Masang Pilipino of former president Joseph Estrada. Reflecting the powers of presidential incumbency, it is no surprise that Rep. Martin Romualdez, a cousin of Marcos, is the House Speaker, and the eldest presidential son, Rep. Sandro Marcos, gets appointed as a senior deputy speaker. Consistent with political practice, the House representatives who ran under different parties typically support the incumbent president’s legislative agenda, not wishing to be left out of choice committee positions and other perks and largesse linked with ruling coalition membership.

Moreover, since the lower house members need to be reelected every three years for a term limit of nine continuous years in office, they generally seek presidential support for these expensive electoral contests or avoid antagonizing the incumbent executive who enjoys a six-year office term. Given these political dynamics, the administration passed the highly contentious Maharlika Investment Fund law in record time while the lower House also fast-tracked the approval of its version of proposed Constitutional changes.

Historically, the Senate has enjoyed greater institutional independence from the presidency because of its six-year term with reelection for another six years of continuous service. Moreover, the senators have a national electoral constituency and are generally more conscious of the national impact of their legislative behavior. They are generally less vulnerable to outright presidential pressure compared with their counterparts in the lower house. In the current Senate of the 19th Congress, three-fourths of the members come from political families with combinations of a mother and son (Villars), two siblings (Alan and Pia Cayetano), and two half-brothers (Joseph Ejercito and Jinggoy Estrada). The Senate has also been a breeding ground for presidential aspirants with the member’s initial advantage of a national constituency and name recall, especially for the elected celebrities.

Reflecting once again the weakness of party affiliations as in the Lower House, the senators tend to vote as individuals depending on the policies being discussed. However, Sen. Risa Hontiveros has consistently shown an oppositionist stance, usually joined by Sen. Aquilino Pimentel III. Senators Christopher “Bong” Go, and Ronald dela Rosa are diehard Duterte loyalists owing to their past close ties with the former president as trusted presidential assistant and Philippine National Police Chief, respectively.

An interesting phenomenon in the current Senate is the adversarial stance of Sen. Imee Marcos on major policies identified with her brother, including the controversial Maharlika Investment Fund, the current proposal to change the constitution, and the president’s pro-American foreign policy pivot. In the worsening conflict between Marcos and Duterte, Sen. Imee Marcos has been perceived as playing both hands ultimately for the Marcos interests or as a mediator, at times. However, she may also be doing this out of pique due to her reported exclusion from the inner policy-making circle of her brother. A potentially consequential event could happen in the coming 2025 mid-term elections if former president Duterte decides to run for a Senate seat. In all the surveys on the possible senatorial candidates in 2025, the former president easily makes it to the top winning column. Duterte’s closest allies in the Senate, Senators Bong Go and Bato de la Rosa who are running for reelection in the 2025 elections are also in the winning circle as shown by the latest surveys.

Most Urgent National Concerns

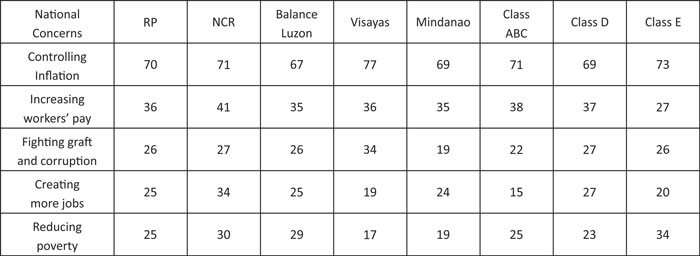

The March 2024 survey by Pulse Asia showed that the most urgent national concerns of the people focus on addressing economic problems but also fighting graft and corruption in government. In the survey, the top five most urgent national concerns perceived by respondents included:

Pulse Asia Research Inc., 6 – 10 March 2024

(in percent/multiple response, up to 3 allowed)

In the same month (March 11-14), the OCTA Research survey also showed that economic concerns are the people’s most urgent concerns. In this survey, the top five urgent national concerns included: 1) controlling the increase in prices of basic goods and services, 66%; 2) increasing wages or salaries of workers, 44%; 3) access to affordable food like rice, veggies, and meat, 44%; 4) creating more jobs, 33%; and 5) reducing poverty, 30%.

Interestingly, in both surveys, only 1% of respondents considered “changing the constitution” an urgent national concern.

Weak State Capacity and Institutions: Corruption and Low Absorptive Capacity

Like all presidents before him, President Marcos faces systemic governance problems with the country’s debilitating tradition of weak state capacity and governance institutions. This endemic weakness is rooted in a system where the civilian and military bureaucracies lack the professionalization and insulation from the partisan interventions of far more powerful elected officials at both the local and national levels of governance. Various anti-corruption laws and executive orders are in place, but these are not enforced effectively. Moreover, civil society monitoring of public officials' performance has been difficult and limited. These conditions explain the lack of accountability and the impunity that corrupt and abusive public officials enjoy. Two enduring manifestations of these weak governance institutions lie in rampant corruption and the low absorptive capacity of government agencies.

The Philippines continues to lag behind its peer Southeast Asian neighbors on the latest global Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) in 2023. On a scale of 0 to 100 in the CPI with 0 as highly corrupt and 100 as very clean, the Philippines received a rating of 34 compared with the following major ASEAN countries: Singapore 83, Malaysia 50, Vietnam 41, Thailand 36, and tied with Indonesia at 34. These less corrupt countries have also demonstrated better indices of economic growth and development. About four years ago, the World Bank and the Office of the Philippine Ombudsman estimated that about 20% of the national budget is lost to corruption each year.

Institutionalized corruption in the country occurs in the very process of budget preparation each year. In 2013, the Supreme Court ruled unconstitutional the long-time practice of legislators who enjoyed “pork barrel” funds (Countrywide Development Fund and Priority Development Assistance Fund) which were lump-sum appropriations they could use for projects they deem worthy for their constituents. This practice led to massive corruption especially when a scheming businesswoman, Janet Lim Napoles, in collusion with legislators, orchestrated the use of these funds for ghost NGOs for which the involved members of Congress received huge kickbacks. After this nefarious practice was exposed, the Office of the Ombudsman charged three senators (Juan Ponce Enrile, Ramon Revilla, Jr., and Jinggoy Ejercito Estrada) and various representatives of the lower House with plunder and graft cases.

However, the annual budget preparation in both the House and the Senate continues to have questionable appropriation insertions. These appropriations bypass the normal processes of discussions and debate in both Houses and tend to favor certain agencies whose projects when implemented could work to the advantage of well-connected legislators and their networks. In the 2024 budget approved by Congress and the President, another controversial last-minute insertion was the P449.5 billion “unprogrammed appropriations”. Reacting to these “unprogrammed appropriations” Senate Minority Leader Aquilino Pimentel III pointed out that this insertion was unconstitutional because Congress is prohibited from increasing the budget as proposed by the executive branch. In response, Budget Secretary Amenah Pangandaman said that “unprogrammed funds” are constitutional since these could only be released with additional revenues.

A questionable transfer of funds from the Office of the President (OP) to the Office of the Vice President (OVP) Sara Duterte took place during the first year of the administration. The OP transferred some of its contingent funds in the amount of P125 million to the OVP to be used as confidential expenses by the latter. This amount was reportedly used by the OVP in just 11 days in December 2022. Questioning the legality of this fund transfer, the opposition Makabayan bloc in the lower House and two other groups of legal and economic experts filed suits in the Supreme Court challenging the constitutionality of the fund transfer. The same case sought to require the Commission on Audit to audit the fund’s disposition like any other public fund and compel VP Duterte to return the funds to the national treasury.

Another contentious issue in the 2024 budget preparation focused on whether civilian agencies of the government can be provided with confidential and intelligence funds (CIFs) normally given only to the Office of the President and agencies doing work on military and security-related issues. This was triggered by the request of the Offices of the Vice President and the Department of Education, both headed by VP Sara Duterte, for P650 million in confidential funds. After much congressional debate and intense public scrutiny, the approved final version of the 2024 budget stripped civilian agencies of their proposed CIF appropriations or realigned these for agencies doing defense and security-related functions. An exception to this decision was the Office of the President which routinely receives its CIF. However, in terms of governance transparency, the use of CIFs undergoes an auditing process by the Commission on Audit whose results are not easily accessible to the public.

Together with the country’s endemic problem of corruption, the low “absorptive capacity” of many government agencies in utilizing funds allocated for their use is another major indicator of low state capacity. Some recent cases exposed during the Senate budget hearings in 2022 included the following unused funds allocated to government agencies: the Philippine Center for Postharvest Development and Mechanization (PhilMech) spent only P159 million of its P5 billion budget meant to help rice farmers improve their harvests; the Bureau of Soils and Water Management failed to spend an allocation of P1.1 billion to develop composting facilities for biodegradable wastes to help them cope with high fertilizer costs. Both flagged agencies are attached to the Department of Agriculture. Moreover, the Commission on Audit also found out that in 2020, 2021, and 2022, one-third of the Agriculture Department’s expenses were either unliquidated or unexplained.

Other similar cases of low absorptive capacity exposed in the 2022 Congressional budget hearings were the following: the failure by the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG) to spend P577 million of its P4.03 billion budget for Covid-19 response measures in 2021. The much-criticized National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC) was found by the House Committee on Appropriations to have completed only 2 percent of its 2022 projects while the remaining 98 percent were still under the procurement or pre-procurement stage by the end of December 2022! Worse, the Department of Interior and Local Government (DILG) was also awarded P400 million to “assess and evaluate the activities” of the NTF-ELCAC when this agency had not even submitted an accomplishment report in 2021 and 2022!

To address problems of corruption and low absorptive capacity, the administration has sought the digitalization of government processes. For instance, the Department of Information and Technology (DICT) was created in May 2016 to serve as the country’s main administrative agency to plan, develop, and promote the national digital development agenda. During the last six years, the DICT record leaves much to be desired. No less than the new DICT secretary Ivan Uy admitted in a budget hearing before the House of Representatives in September 2022 that the department like many other government agencies suffers from very low utilization of funds. In the same hearing, he admitted that the DICT was able to use only 25 percent of its previous appropriations. Aiming to set up 105,000 free public WI-FI spots with a 12-billion-peso allocation from Congress, the department was able to establish only 10 percent of the sites with only 10 percent operating. In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, the DICT’s failure to put up these public internet sites of critical use to the education sector further accentuated what is now known as the “learning poverty” crisis in the country, especially for K-12 students.

Showing a close correlation between the low utilization of budgeted funds and corruption, it turns out that these billions of unused funds are usually conveniently “parked” in two government agencies that have already attained notoriety because of their corrupt practices. These two agencies, the Philippine International Trading Corporation (PITC) and the Procurement Service of the Department of Budget and Management (PS-DBM), have served as convenient shelters for unused agency funds to escape accountability. At the height of the pandemic, the PS-DBM officials served as facilitators in the Pharmally Pharmaceutical procurement scandals and also as accomplices with some Department of Education officials in the gross overpricing of laptops meant for K-12 teachers.

Another related program to improve the digitalization of government services was the enactment in 2018 of the Ease of Doing Business and Efficient Government Services Delivery Act (Republic Act No. 11032). The same law created an Anti-Red Tape Authority (ARTA) to oversee the implementation of its processes. In committing his administration to digitalizing, harmonizing, and standardizing government data, President Marcos stressed that the ARTA, in coordination with other government agencies, will pursue the National Policy on Regulatory Management System (NPRMS) to provide a common framework for good regulatory practices, and enforcement and compliance strategies. Interestingly, Marcos issued an executive order fully consistent with the provisions of ARTA but also created a new “Green Lane for Strategic Investments” upon the Department of Trade and Industry’s initiative. Some have pointed this out as a recognition of some of the limitations of ARTA and others suggest that ARTA’s expansive powers have provoked some pushback from other government agencies, including at one time, the Office of the Ombudsman.

The enduring problems besetting the professionalization of the country’s civilian bureaucracy are dramatized by examining briefly the plight of the Department of Education (DepEd) which has the biggest number of government workers. This department is now headed by the Vice-President, Sara Duterte, who has no background or work experience in the educational sector. Even before the pandemic, K-12 students already performed badly in various international student assessments with about 80 percent of them failing basic tests in mathematics, science, and reading comprehension. While this dismal showing is explained by many factors including poverty, poor nutrition, and the inadequate provision of key learning infrastructure (classrooms, appropriate curricula, access to information technology, etc.), the teachers as the key human learning resource in the educational process play a decisive role. The reality on the ground is that the country’s K-12 teachers, about a million of them in public and private institutions, continue to be underpaid and overworked.

More disturbingly, a 2022 study by the Philippine Business for Education and the government think tank, the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) analyzed a teacher-licensure database for 12 years and found that low teacher quality was highly correlated with poor performance of students. These findings highlight the need for quality interventions during both “preservice and in-service periods” for teachers to improve their teaching competence. Moreover, these quality interventions in training programs must necessarily be accompanied by adequate institutional improvements in the teachers’ living standards and work conditions for such measures to be sustainable. Finally, during Marcos’ first year, the budget approved for the DepEd headed by Vice-President Sara Duterte also included an unprecedented P150 million allocation for confidential and intelligence funds (CIF). Opposition legislators strongly pointed out that the DepEd has no mandate for this kind of allocation and the funds could have been better used for educational infrastructural development and further professionalization of the teachers.

Showing a lack of urgency in addressing problems, the president took 19 months to appoint the full-time heads of the Department of Agriculture (DA) and Department of Health (DoH). In the aftermath of the COVID-19 crisis that devastated the country’s economy, health, and social services, this indecisiveness in appointing key cabinet officials proved costly. Much of the food-related crisis, especially of the high prices of sugar and rice that hit the country in the administration’s first year took place while Marcos appointed himself the acting agriculture secretary. The absence of a full-time and competent cabinet secretary exacerbated these problems although the overall food crisis is rooted in the long-time structural backwardness of the agricultural sector. In one of his official announcements to address the country’s high inflation rate, Marcos promised to bring down the price of rice to P20 per kilo. Almost two years later, this staple food in its regular-milled form continues to sell at an average of about P42 per kilo. National Statistician Claire Dennis Mapa confirmed that rice inflation reached a 15-year high of 24.4% in March 2024 and this rice price hike is the biggest contributor to high inflation reported at 3.8% in the same month. The Philippines is the world’s biggest rice importer and has a rice import dependency ratio of about 23%.

Human Rights and the International Criminal Court (ICC)

President Marcos faces a bloody legacy of human rights abuses and a brutal war on illegal drugs conducted by the Duterte administration. The Philippine National Police (PNP) admits officially to 6,000 cases of extra-judicial killings (EJKs) related to the war on drugs during Duterte’s presidency but human rights organizations provide a much higher figure of victims at about 30,000. Out of 52 cases reexamined and submitted for prosecution by the Justice Department only two police personnel had been convicted by the courts.

Conscious of rebranding his image locally and globally, President Marcos in his 2023 State of the Nation (SONA) address announced that his campaign against illegal drugs is “now geared towards community-based treatment, rehabilitation, education, and reintegration to curb drug dependence . . .” In March of this year, the government announced that survivors and victims of EJKs and other grave human rights abuses may now seek compensation under a Department of Justice program in coordination with the Commission on Human Rights (CHR). Seeking an enhanced global leadership role, Marcos is also pressured to abide by United Nations global standards on human rights. This year, the Philippines chairs the UN Commission on the Status of Women and has made a bid for a seat in the UN Security Council in 2027-2028.

However, the human rights situation on the ground deserves serious monitoring of Marcos’ claims to gain credibility. In his first 14 months in office, 397 people were killed in “drug-related violence” as reported by the Third World Studies Center of the University of the Philippines. Moreover, the practice of “red-tagging” by state authorities or branding activists and peaceful dissenters as communists or terrorists leading to their arrest, abduction, or killing, continues with impunity.

The observance of human rights in the country remains daunting with the continuing existence of a legal and political infrastructure put in place during Duterte's presidency that endangers the exercise of constitutional civil and political rights: the Anti-Terrorism Law passed in 2020 and the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC) created in 2018.

In its original form, the Anti-Terrorism Law provided an overly broad definition of terrorism and gave the Anti-Terrorism Council an equally broad mandate to designate and detain persons alleged to be terrorists. In response to at least 37 petitions, the Supreme Court (SC) declared unconstitutional two provisions of the law in 2021. First, the Court ruled that the Anti-Terrorism Law’s definition of terrorism was unconstitutional “for being overbroad and violative of freedom of expression.” In its ruling, the SC declared that terrorism, as originally defined in the law, should now read as actions that “shall not include advocacy, protest, dissent, stoppage of work, industrial or mass action, and other similar exercises of civil and political rights.” The SC also declared as unconstitutional the power of the Anti-Terrorism Council to designate a person or group as terrorists based on a request by another country following relevant UN Security Council resolutions. However, the SC also upheld the constitutionality of other controversial provisions of the law including warrantless arrests and detention of alleged terrorists for up to 24 days, unlawful surveillance, freezing of assets of suspects, and other provisions inconsistent with international law and standards and open to abuse by authorities.

On the other hand, the NTF-ELCAC has served as the main executive instrument for the red-tagging of many activists and civil society leaders, including media personalities, lawyers, and judges. This systematic red-tagging by the NTF-ELCAC has persisted up to the Marcos administration and has led to many arbitrary arrests, detention, and extrajudicial killings with impunity. The NTF-ELCAC is supposed to use its budgetary funds to provide various infrastructure projects and assistance to individuals or families in barangays certified by the task force as cleared of rebel control or influence. However, this function is better performed by many other line agencies of the government and local government units. Moreover, the NTF-ELCAC continues to face problems of unliquidated and misused billions of funds, possibly serving as another venue for corruption and resource leakage.

Showing the same concern about the continuing impunity in human rights-related cases under Marcos, six UN special rapporteurs made public a letter dated 10 October 2023 seeking an explanation for alleged human rights violations under the incumbent president. They expressed “serious concern about the seemingly broad and unchecked executive powers . . . particularly the discretion of the Anti-Terrorism Council to designate individuals and organizations as “terrorist” and the Anti-Money Laundering Council to adopt targeted financial sanctions thereafter.”

At the end of her ten-day visit in February 2024, Ms. Irene Khan, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on freedom of expression and opinion, called on the government to abolish the NTF-ELCAC. She stressed that the task force was created in a “different context” six years ago, making it outdated. Khan further pointed out that the continuing operation of the NTF-ELCAC “does not take into account the ongoing prospects of peace negotiations” after the signing of a joint statement in November 2023 between the government and the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP) about the revival of peace talks. In a meeting with House leaders, Khan also urged the legislators to pass three pending bills to promote freedom of expression and opinion. These bills include the Human Rights Defenders Bill which seeks more protections for human rights workers; the Media Welfare Bill which calls for “humane conditions at work for all media personnel;” and the bill to decriminalize libel.

The end of the Duterte presidency has also mitigated the atmosphere of fear and terror that crippled both civil society and the governmental organs of accountability, especially the judiciary and the Commission on Human Rights. Perhaps, the most dramatic case reflecting the judicial system’s awakened sense of independence from presidential power was the grant of bail to former justice secretary and senator Leila de Lima in November 2023 after being detained for almost seven years on trumped-up charges of drug trafficking.

In 2023, the International Criminal Court (ICC) rejected the Philippine government’s petition to stop the investigation of the thousands of extrajudicial killings committed in the war against illegal drugs during the administration of President Duterte. The ICC investigation covers extrajudicial killings in the context of the “war on drugs campaign” in the Philippines from 1 November 2011 to 16 March 2019 when the Philippines withdrew from ICC membership on Duterte’s initiative. The ICC has proceeded with its probe but without government authorities' official cooperation or consent. Early this year, Marcos announced that he does not recognize the jurisdiction of the ICC in the country and “will not lift a finger to help any investigation that the ICC conducts.”

Former senator Antonio Trillanes IV reported in April 2024 that more than 50 active and retired police officers who served during the Duterte administration are on the list of people under investigation by the ICC. Reacting to Trillanes’ revelation, the PNP affirmed that it would not recognize the ICC’s jurisdiction over the drug war probe. Stressing the government’s opposition to the ICC investigation, the Department of Justice through its spokesperson and Assistant Secretary Jose Clavano IV also asserted that police officers and government officials who will cooperate with the ICC investigation will face administrative charges and possible dismissal from the service.

Like many critical events in the country, the rapidly changing political conditions on the ground would define the progress and outcome of the ICC investigation into the extrajudicial killings. While Marcos has officially announced a policy of non-cooperation with the ICC, a deepening conflict with former president Duterte could ultimately push the former to use the ICC investigation to immobilize Duterte and his allies politically. However, this action would signal an irreparable rupture between the most powerful and ambitious political dynasties, impacting the country’s stability.

Constitutional Change

Except for President Corazon Aquino (1986-1992) and her son, Benigno Aquino III (2010-2016), all the other presidents after the ouster of the dictator Marcos in 1986 sought to amend unsuccessfully the 1987 Constitution. In March 2024, the House of Representatives fast-tracked the approval of the Resolution of both Houses No. 7 (RBH-7) that seeks to amend certain economic provisions of the Constitution seen as too restrictive for the entry of foreign direct investments. The Senate version of the same resolution (RBH-6) has yet to pass. Resisting pressures from the lower House, the Senate leadership has stated that more public consultations are needed considering recent surveys showing that about 88% of the electorate are opposed to changing the constitution.

The Resolution of both Houses (RBH-6 and 7) proposes the following amendments to the Constitution by adding the expedient qualifying phrase “unless otherwise provided by law” to Articles 12, Section 11; Article 14, Section 4 (2); and Article 16, Section 11 (2). These pertinent Articles and Sections require the majority ownership by Filipinos of the following institutions: public utilities by 60%, educational institutions by 60%, and advertising by 70%, respectively. In short, the proposed amendments seek to amend the current limitations on the participation of foreign capital in these three sectors by allowing Congress the legislative flexibility of approving the expedient phrase “unless otherwise provided by law” for each of the targeted constitutional provisions.

In the public discussions and Congressional committee hearings on these proposed amendments, both procedural and substantive issues were raised. The Resolutions of both Houses provide for a three-fourths voting procedure on the proposed amendments without specifying if the voting is done separately by the House and the Senate. This is an unresolved constitutional ambiguity in the current constitution because the three-fourths voting procedure was originally meant for a unicameral body but the final constitution approved was that of a bicameral body. If the voting were done by both houses convening and voting as one body, the Senate’s voting strength of only 24 senators would be easily swamped by the 316 members of the current House of Representatives. Not surprisingly, the Senate will always insist that the voting is done separately.

The Resolutions of both Houses also assume that constitutional provisions could be amended by the regular legislative lawmaking powers of Congress such as voting on expedient phrases, “unless otherwise provided by law,” that are added to the existing provisions. As pointed out by former Supreme Court Chief Justice Reynato S. Puno, the constitutionality of such an action will most likely be challenged before the highest court.

The key proponents of the current moves to amend the economic provisions of the Constitution argue that the country needs more foreign investments for development and that the proposed amendments are necessary measures. Two interrelated important issues need to be clarified here. First, will the lifting of equity provisions in the current Constitution result in more foreign direct investments (FDI)? Second, will more FDI necessarily result in positive effects on the economy?

A recent paper by a group of faculty members from the UP School of Economics on 11 April 2024 provides an instructive set of empirical findings on these issues. On these two issues, the paper states:

“A fuller appreciation of the given evidence shows that lifting equity restrictions is not a necessary condition for explaining the inward stocks of FDI . . . including the Philippines. While restrictive equity rules may represent a hindrance to FDI, their potential effects are small and sometimes insignificant in comparison to other explanatory variables such as ease of doing business, physical infrastructure, and perceived corruption.”

“. . . consistent empirical evidence of the positive effects of FDI on host economies has proved elusive and that knowledge and technical spillovers from FDI are highly context-specific, not unconditional, and not without cost.”

Addressing the same issues, the think tank, Ibon Foundation, affirms that large foreign investment is neither necessary nor sufficient for development. In relative terms, the Philippines now has more FDI than China, South Korea or Taiwan did during their economic take-off in the 1970s and 1980s. Ibon Foundation further points out that annual foreign investment inflows have significantly increased from an annual average of 0.5% of GDP in 1980-1984 to 2.7% of GDP in 2021-2022, but with an insignificant impact on the economy. For instance, 100% ownership is allowed in the manufacturing sector, and yet this industry had the smallest GDP share in 75 years at 17.6% for the first three quarters of 2023. Finally, the think tank counsels that a clear program of national industrialization is the more urgent problem to be addressed for economic growth and development to be more inclusive and sustainable.

Much of the discussion on charter change has so far focused on the economic provisions. But lurking at the margins are the more critical issues that are closer to the interests of the powerful players and political families. These are the political amendments on existing term limits or the shift to a unicameral and parliamentary system that could surface once both houses of Congress have finally agreed to formally activate the charter change process. As one representative aptly noted, once Congress sits as a constituent assembly for charter revision, all provisions are potentially subject to change.

The Marcos-Duterte Alliance: A Break-Up Foretold

From its birthing in the contentious 2022 presidential election, the Marcos, Jr. -Sara Duterte alliance bore the seeds of its predictable unraveling. A convenient electoral union between the country’s two most powerful political clans, the alliance was riven by deep conflicts of interest that were bound to explode sooner or later. What surprised many was the fracturing of the alliance very early in the inevitable positioning for strategic advantage in the country’s political arena.

Brokered largely by the machinations of former president Gloria Macapagal Arroyo (GMA) and Senator Imee Marcos, the alliance was never endorsed by the Duterte patriarch, former president Rodrigo R. Duterte. Openly showing his contempt for Marcos for being unfit for the job, Duterte wanted his daughter, then Davao City Mayor Sara, to run for the presidency after he failed to convince his close allies to run for the highest post in the land.

The fragility of the alliance lies in one fact about Philippine politics: the unending contest for clan power and dominance that in the past went beyond the fragile civilities of electoral contestation.

Initial Cracks in the Alliance

In the assignment of choice positions in the Marcos administration, the initial tensions in the alliance surfaced when both GMA and Sara failed to get their preferred political recompense. Befitting her political gravitas and her role in forging the winning alliance, GMA had her eyes set on the Speakership of the House while Sara wanted to head the strategically critical Department of National Defense.

Not surprisingly, the House Speakership went to Rep. Martin Romualdez, a first cousin of Marcos. At the same time, Sara Duterte was appointed the Secretary of the Department of Education, a position ill-suited to her previous training and work experience. A former president and House Speaker herself, GMA was appointed as the senior Deputy House Speaker, the de facto No. 2 position in the House but also a largely ceremonial office.

An unexpected discord in late May 2023 in the ruling coalition saw the demotion of GMA to just one of the nine Deputy House Speakers. Several reasons surfaced to explain Arroyo’s loss of favor. First, Arroyo was suspected of plotting a House coup against Speaker Romualdez's leadership which she strongly denied. Second, GMA’s active participation in the official foreign trips of Marcos provoked charges of upstaging the president with GMA’s much wider experience in international policy networks. Moreover, Arroyo had signaled a more nuanced balancing of the country’s foreign policy options vis-à-vis the United States and China as against Marcos’s definitive pivot to the country’s former colonial power.

In response to Arroyo’s demotion in the House, Vice President Duterte immediately resigned from the ruling Lakas-Christian Muslim Democrats (Lakas-CMD) party where she serves as co-chair. The vice president decried “political toxicity” and “execrable political power play” while affirming her support for President Marcos. However, in a telling revelation about the events leading up to her decision to run for the vice presidency with Marcos, Duterte affirmed that Lakas-CMD party president and now House Speaker Romualdez had “absolutely nothing to do to with my decision to run for vice president.” Duterte also confirmed that it was Senator Imee Marcos, the president’s sister, who “eventually persuaded me to run as vice president and it was a decision sealed only after President Marcos agreed to the conditions I set before running for VP.” Vice President Duterte, however, was silent about the conditions she set for agreeing to run with Marcos.

Widening Fissures in the Coalition

The ongoing investigations by the International Criminal Court (ICC) on the massive killings under Duterte pose a big problem because the process is no longer under the complete control of either Marcos or the former president. No doubt an existential threat to the Dutertes, any progress of the ICC investigation and trial of the drug war-related killings would wreck any remaining shred of détente between the two families.

Marcos has asserted that his administration “will not assist in any way, shape, or form, any of the investigations that the ICC is doing here in the Philippines.” However, Marcos also faces increasing pressure within the country and the international community to provide justice to the thousands of human rights victims during Duterte’s presidency. Moreover, Marcos knows that the ICC investigation is a sword of Damocles that he can manipulate against the Dutertes if any red lines are crossed.

Adding fire to the widening rift between the two families was the decision by Congress to exclude from Vice President Sara’s budgetary appropriation the huge intelligence and contingency funds she enjoyed as Department of Education Secretary. Reacting angrily to this congressional rebuff, former President Duterte accused Congress of being the most corrupt institution in the country and threatened to kill the most articulate critic in the House, ACT party-list representative France Castro of the Makabayan bloc.

Duterte’s confrontation with Congress reached new heights with the involvement of the controversial Sonshine Media Network International (SMNI) owned by a close ally, Apollo Quiboloy, and founder of the Kingdom of Jesus Christ (KOJC) religious sect. SMNI provided Duterte with a regular program that allowed him to reach a bigger public and was aided by diehard supporters, Lorraine Badoy and Jeffrey Celiz, both notorious for their red-tagging practices. These two were cited in contempt and detained by the House for their refusal to divulge their sources for allegations of huge traveling expenses enjoyed by Speaker Romualdez. All these questionable activities of SMNI led to the indefinite suspension of its franchise.

Dramatizing the ties that bind Duterte and Quiboloy, the former president was named the administrator of the besieged Kingdom of Jesus Christ with the legal authority to handle all the concerns of the church. This is a move to protect Quiboloy from the various criminal charges that he now faces abroad and locally. Quiboloy has been indicted by a federal grand jury in California for conspiracy to engage in sex trafficking and bulk cash smuggling and issued a warrant of arrest in November 2021. Moreover, the Philippine Department of Justice filed a qualified human trafficking case against Quiboloy with no recommended bail. Issued a subpoena by both Houses of Congress to face investigation, Quiboloy has refused to do so. He is now facing two warrants of arrest issued by the Regional Trial Courts of Davao City and Pasig City. Quiboloy has gone into hiding and the PNP and National Bureau of Investigation forces have so far failed to locate and arrest him.

On almost every policy and program associated with Marcos, Duterte has found himself at cross purposes with the incumbent president. Duterte and Vice President Sara have condemned the agreement between the National Democratic Front and the government to resume peace talks, maligning this as an “agreement with the devil.” Some minor unrest in the military has been attributed to retired military officers linked with the former president.

On foreign policy, both the former president and Vice-President Sara continue their close association with China while President Marcos has decisively pivoted to the country’s traditional close links with the United States. This decision by Marcos has enabled him to sidestep the remaining criminal charges against his family in the United States while pursuing a military-based alliance in response to the conflict in the South China Sea/West Philippine Sea.

In the most dramatic public display of this increasing enmity between the two families, the Dutertes held a public gathering in Davao City in late January 2024. This was deliberately planned to coincide with President Marcos’ formal launch of his Bagong Pilipinas (New Philippines) movement, an image rebranding project with echoes of his late father’s Bagong Lipunan. In this mass gathering in Davao City, the Dutertes except for the more calculating Vice President Sara, openly attacked Marcos accusing him as a “drug addict,” called for his resignation, and stressed that the charter change agenda pushed by the president’s allies in Congress is meant to perpetuate the incumbent officials’ rule.

Replying in kind, Marcos said that former President Duterte’s long-time use of the painkiller drug, Fentanyl, might have impaired his cognitive ability. A few days after these open attacks against President Marcos, the former president threatened to revive a new movement for the secession of Mindanao. His close allies, including former House Speaker and Davao del Norte representative Pantaleon Alvarez, have echoed this secessionist threat and called on the armed forces to withdraw their support for Marcos but these calls have been rejected by the PNP and AFP leaderships. Adding further drama to this deepening conflict, First Lady Liza Araneta Marcos said she felt hurt when Vice President Duterte was reportedly seen laughing during the January 2024 public rally event in Davao City when President Marcos was called a drug addict. The incumbent president describes his relationship with the Dutertes as “complicated” but also said that his working relationship with Vice President Sara “hasn’t really changed.”

As the Marcos administration starts its mid-term cycle, it faces an increasingly volatile environment of economic recovery and local and global conflicts that threaten the stability of its rule. These points of contention have further deepened the conflict between the country’s two most powerful and ambitious political clans leading to political realignments that will be put to a test in the 2025 mid-term elections unless these tensions erupt earlier into extra-parliamentary confrontations. In such critical conjunctures, new openings and opportunities for progressive substantive changes could also emerge.

>>> Click here to DOWNLOAD the article

- Two Years of the Marcos Presidency: Political and Governance Trends

- Marcos courts war by enabling US provocations; El Niňo hits hard, amnesty for rebels rejected anew

- VICTORY OR DEAL? Russia-Ukraine war drags out

- MARCOS EXPANDS DEFENSE ALLIANCE VS CHINA

- CenPEG marks 20th founding with public forum on Cha-Cha

- PIVOTAL RIFT IN RULING COALITION

- BUMPY ROAD TO PEACE TALKS

Jeepney drivers fight for their last breath; Marcos OKs spotty spending plan - PEACE TALKS, ICC PROBE ON DUTERTE, CONTINUING MARITIME TENSIONS DOMINATE NOVEMBER EVENTS

- CenPEG CALLS FOR PEACE AND HUMANITARIAN SUPPORT AMID ESCALATING CONFLICT IN MIDDLE EAST, End the US-Israel War of Aggression vs. Palestine

- A Broad Perspective on the Current Controversy about Election Return Transmissions In Particular and on Our Voting Automation Issues In General

- The First Year of Marcos Jr.

- The US global war machine in the PH

- Marcos State Visit to US Firms up Overall Ties; Administration Ruling Coalition Faces Discord

- Marcos, Jr.’s pivot to the U.S. deepens

- South China Sea tops Biden-Marcos summit

- Philippines split over increased U.S. military presence

- China-Russia ties on high note

- What are geopolitical implications of U.S. defense chief's visit to the Philippines?

- Configuring Philippines-China ties under Marcos, Jr.; Philippine Development Plan and controversial funds

- Is there prospect for the hybrid election system (HES)?

- MARCOS, JR. FACES GRINDING WOES; ARE REFORMS POSSIBLE?

- Marcos, Jr. pivots to the US; faces tough economic challenges

- CenPEG’s 16th book launched

- Sisa’s Vengeance: Jose Rizal’s Sexual Politics & Cultural Revolution

- Marcos, Jr. in cryptic ties with China as he commits to U.S. defense alliance

- Philippines - a geostrategic battleground?

- The other side of Shinzo Abe: historical revisionism, denial of war crimes

- Rightsizing and reengineering bureaucracy

- Nancy Pelosi’s history of belligerency on Beijing

- Indonesian leader's China visit: Elevating bilateral relations

- 14th State of the Presidency

The Marcos, Jr. Presidency: Key Challenges from the People's Perspective - The May 2022 Elections and the Marcos Restoration: Looking Back and Beyond

- Rethinking ASEAN ties with U.S., signs of another Cold War may be in the air

- A quest for peace in Europe

- Maelstrom Over the Killing Fields

- The Russians are coming!

Center for People Empowewrment in Governance (CenPEG), Philippines. All rights reserved