Posted by CenPEG.org

22 June 2022

The May 2022 Elections and the Marcos Restoration: Looking Back and Beyond

In the country’s post-EDSA political history since 1986, the May 2022 election marks the first time the two most powerful political families running as a team won the presidency and vice-presidency with majority votes. Stunningly, the Marcos family is once again on top of the country’s political establishment with the proclamation by Congress of Ferdinand R. Marcos, Jr. as the 17th president of the republic. With Davao City Mayor Sara Duterte as the vice-president, the incoming administration led by Marcos, Jr., is set to define the country’s line of march in what may prove to be the most challenging circumstances in the country’s recent history.

Ousted from power and forced to go into exile after a combined military mutiny and peoples’ uprising in February 1986, the Marcos family systematically plotted a political restoration after being allowed back into the country in 1991, ironically to face corruption charges. As early as 1992, the family jump-started a political comeback with the former first lady, Imelda R. Marcos, running for the presidency, and Ferdinand R. Marcos, Jr. for the governorship of Ilocos Norte, the family’s political fiefdom. Mrs. Marcos lost her presidential bid, receiving a little over 10% of the votes but Marcos, Jr. easily won as governor.

It is instructive to note that in the early 1990s, the broad pro-Marcos national electoral base remained at almost 30%. This figure reflects the combined votes of Imelda Marcos and Eduardo Cojuangco, Jr., the close Marcos crony and oligarch who also ran a losing bid for the presidency in 1992, receiving about 18% of the votes. Looking back, the Marcos bloc could have won the presidency as early as 1992 had Mrs. Marcos and Cojuangco, Jr. joined forces, with their combined total votes of 29% edging out the 24% votes received by President Fidel V. Ramos, supported by outgoing president Corazon C. Aquino.

In retrospect, it also appears that the national electoral base of the Marcoses at about 30% proved to be a reliable resource for their succeeding bids for national positions. In his successful run for the Senate in 2010, Marcos, Jr. received almost 35% of the votes while in his failed bid for the vice presidency in 2016, he got more than 34%. Following this voting trend, Marcos, Jr.’s sister, Maria Imelda “Imee” Marcos also received, about 34% of the votes in her winning bid for the Senate in 2019.

The Presidential and Vice-Presidential Contest: A Victory Foretold?

There exists an uncanny consistency between the pre-election survey results and the final canvassed counts as reported by the Commission on Elections (Comelec). While some election watchdogs and opposition groups continue to cast doubt on the integrity of the automated election system, the unprecedented election results favoring the Marcos-Duterte team require some explanation backed up by some empirical validity or analytic plausibility.

A confluence of different factors helps untangle the events that shaped the final outcome. First, there exists the continuing reality of election bailiwicks rooted in regional-linguistic identities and loyalties as a critical resource base for national candidates. Second, the impact of President Duterte’s position on the campaign especially in light of his continued high survey ratings till the end of his term needs to be evaluated. Third, the extent to which the systematic campaign of disinformation and historical revisionism, especially in social media, impacted voter behavior also needs explanation. Closely related to this factor is the puzzle of why the political narrative and messaging of the Marcoses seemed to have resonated far better with the majority of the voters, especially with the poorer and disadvantaged social classes. Fourth, is the impact of the divided opposition on the campaign and voter choices. Fifth, the overall effect of the huge financial and organizational resources of the Marcos-Duterte team especially with the support of other powerful families and oligarchs, and various local government officials. A final factor requires an examination of the continuing problems and impact of an automated electoral system (AES), especially under the management of a Commission on Elections (Comelec) and a foreign service provider (Smartmatic) whose past and current records have not inspired trust and confidence in the system.

The Regional Distribution of Votes and Election Bailiwicks

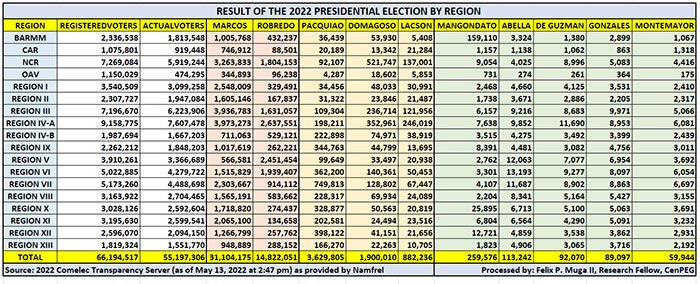

Without addressing for now the many questions raised on the credibility and verifiability of the election returns generated by the vote counting machines and as reported by the Comelec, what can be inferred from the official election results? (See Table 1)

Table 1: Election Returns as Reported by the Commission on Elections (COMELEC) Transparency Server as of 13 May 2022 and provided by the National Movement for Free Elections (NAMFREL). Processed by Dr. Felix P. Muga, CenPEG Senior Research Fellow.

(Click this link or the table for a bigger picture)

On 26 May 2022, Congress acting as the National Board of Canvassers proclaimed former senator Ferdinand R. Marcos, Jr., and Mayor Sara Duterte as the new president and vice-president. With 98.84% or 171 out of 173 of the certificates of the canvas (CoCs) counted, Marcos, Jr. received 31,629,783 votes or 58.77% of the votes counted while Duterte received 32,208,417 or 61.33%. Presidential candidate Vice-President Robredo trailed far behind with 15,035,773 votes (27.94% of votes counted) and her running mate, Senator Francisco Pangilinan had 9,329,207 votes (17.82%).

In comparison with the 2016 vice-presidential contest which also featured Robredo and Marcos, Jr. as the top two candidates, the 2022 presidential contest between them as the leading bets showed a sharp reversal of results. In 2016, Robredo won over Marcos, Jr., by a narrow margin of 278,566 votes after a recount in some contested precincts in a final decision by the Supreme Court in response to an election protest filed by losing candidate Marcos, Jr. In the vice-presidential race in 2016, Robredo won in nine of the regions while Marcos, Jr. prevailed in the other nine, including the CAR, NCR, and the Overseas Absentee Voters.

In the 2022 presidential contest, Robredo won in only two regions, her home region, (Bicol-Region 5), and Region 6 (Iloilo, Capiz, Aklan, Antique, Negros Occidental, and Guimaras), a traditional Liberal Party and an opposition stronghold. On full display in the May 2022 election was the continuing potency of regional bailiwick votes but lopsidedly in favor of the Marcos-Duterte team. In the Ilocano heartland of Regions 1 and 2, Marcos, Jr. enjoyed a huge lead of 3.66 million votes over Robredo, equivalent to an 82% share of the total votes in both regions while the latter received only about 9.5% of the total votes. Showing the same loyalty to a homegrown candidate, the Bicol region also gave Robredo a 1.88 million vote edge over Marcos, Jr. and received a 73% share of the region’s total votes. However, Marcos Jr. still managed to get a 17% share of the Bicolano votes, bigger than the 10% vote share of Robredo in the two Ilocano bailiwicks of Regions 1 and 2.

Predictably, Marcos, Jr. also won handily in the Duterte bailiwick of the Davao provinces (Region 11), with a winning margin of 1.93 million votes over Robredo or a 79% share of the total regional votes. Pacquiao had more votes than Robredo in Region 11, getting an 8% share of the total (202,581) to the latter’s 5% (134,658). Pacquiao also placed second to Marcos, Jr. in Regions 10 and 12, getting more votes than Robredo in these Mindanao areas.

Unlike in the 2016 elections when Robredo won over Marcos in four regions in Mindanao (ARMM, Regions 9, 10, and 13), she ended up losing in all of the Mindanao regions in 2022. Robredo’s big loss in what is now the Bangsa Moro Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) was also surprising since she beat Marcos, Jr. by a wide margin here in 2016 (44% vs. 27%). This region suffered the worst atrocities during the Marcos dictatorship and the common view lingered that this would work against Marcos, Jr. While some of the powerful local clans supported Marcos, Jr., notably the Tans of Sulu and a faction of the divided Mangudadatu families, Robredo also managed to get the endorsement of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), one faction of the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), and the Hatamans of Basilan. However, the Duterte factor, especially in light of the Marcos-Sara Duterte team-up is the new element that was not prominent in the Robredo-Marcos, Jr., faceoff in the 2016 election. In 2022, Marcos, Jr. turned the tables against Robredo by winning 55% of the BARMM votes against Robredo’s 24%.

The voting results in the National Capital Region (NCR) are also instructive in terms of the seeming contradictions and unexpected outcomes. The NCR has the largest concentration of the country’s most affluent families and educated middle classes. Compared with the other regions the NCR has also the easiest access and most exposure to all kinds of media including the various social media platforms. It is the country’s business and financial center and also hosts the most heterogeneous demographic mix of individuals coming from all parts of the country. Traditionally an opposition political center, the NCR, in fact, surprised many with the victory of Marcos, Jr. in the 2016 election where he received 46% of the votes against Robredo’s 28%. With the entry of Manila Mayor Francisco Domagoso “Isko Moreno” in the presidential race in 2022, many expected the election in the NCR to be more competitive. But once again, Marcos, Jr. prevailed in both the NCR and the city of Manila where Isko Moreno managed to win only in his Manila congressional district. For the whole of the NCR, Marcos, Jr. received 55% of the votes against Robredo’s 30% while Moreno struggled with only 9% of the votes. Moreover, Marcos, Jr. also won in all of the 16 cities of the NCR and in the municipality of Pateros. In the two cities in the NCR with the biggest number of votes, Quezon City and Manila, Marcos, Jr. also led by huge margins over Robredo. In Quezon City, Marcos Jr. received 57% of the votes against Robredo’s 34% while in the city of Manila, the former got 40% of the votes compared with Robredo’s, 22%. Mayor Isko Moreno placed second to Marcos, Jr. in Manila with 34% of the votes.

For the election contest at the provincial level, Robredo won in only 15 out of the country’s 81 provinces. Of these 15 provinces, six belong to her home region (Region 5- Albay, Camarines Norte, Camarines Sur, Catanduanes, Masbate, and Sorsogon) and five provinces to a Liberal Party and opposition regional stronghold (Region 6- Aklan, Antique, Capiz, Iloilo, and Negros Occidental). The remaining three provinces that provided Robredo with winning margins included Rizal, Quirino, and Biliran. Robredo won in three of the top 10 vote-rich provinces, (Negros Occidental, Iloilo, and Rizal) but only by an average winning margin over Marcos, Jr. of 140,000 votes. In contrast, Marcos, Jr. posted an average winning margin of 608,000 votes over Robredo in the seven other top-10 vote-rich provinces (Cebu, Cavite, Pangasinan Laguna, Bulacan Batangas, and Pampanga). For instance, in these seven provinces, Marcos, Jr. led Robredo by the following huge margins of victory: Pangasinan, 1.12 million votes; Cebu, 897,313; Bulacan, 643,894; Cavite, 479,154; Laguna, 418,862; Batangas, 381,431; and Pampanga, 310,863.

What seems incredulous about the final Comelec results is that Robredo is shown to have added only 601,863 thousand votes to her 2016 total or a measly 4% increase. In contrast, Marcos, Jr. added 17,489,532 million to his 2016 votes or an increase of 124%!

Explaining the Marcos, Jr.-Sara Duterte Electoral Victory

Long supported by historical data on electoral behavior in the country, the regional-linguistic ties of candidates with voters as seen in voting bailiwicks continue to be a critical factor in voter preferences. In the 2022 presidential elections, these regional bailiwicks proved to be formidable factors once again as shown in the initial advantage enjoyed by Marcos, Jr. and Sara Duterte with the melding of their voting strongholds, the so-called “solid North and solid South” votes. Comparing the voting strength of their tested regional bailiwicks (Regions 1 and 2 for Marcos plus Region 11 of the Dutertes vs. Regions 5 and 6 for Robredo), Marcos, Jr. immediately gained a 1.8 million advantage over vice-president Robredo. But the key question lies in explaining why the Marcos-Duterte team also dominated in all of the regions outside of the two regional bailiwicks won by Robredo since bailiwick votes alone cannot explain the final outcome except in closely contested elections.

High Trust Ratings for President Duterte and Election Impact

A confluence of a number of factors contributed to defining the final election verdict. The continuing high trust and performance ratings of President Duterte up to the end of his term impacted voter preferences. As shown by the country’s electoral record since 1986, a presidential candidate endorsed by or closely associated with the outgoing president with low trust and performance ratings usually ended up losing the election. The only exception to this trend appears to be the victory of the Aquino administration-backed Fidel V. Ramos in the 1992 election in a closely contested match marred by allegations of massive fraud and vote-buying. Unlike his predecessors who all ended their terms with low trust ratings below 50% (as low as 10% for Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo), President Duterte sets a precedent with an average high trust rating of not less than 70% for his six years in office. As shown by all credible public opinion survey groups, Duterte maintained these high ratings even during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic. Even the allegations of coddling close allies charged with massive corruption (Pharmally scandal), and the red-tagging of opposition groups and personalities did not dent his high trust ratings. In terms of voter preferences, the high trust ratings given to the outgoing president apparently translated to electoral support for the team (Marcos, Jr.-Sara Duterte) perceived to be most closely aligned with the persona and policies of the outgoing president and administration.

While Mr. Duterte openly expressed his misgivings about the candidacy of Marcos, Jr., calling him a “weak leader” with no significant achievements, he did not also endorse an alternative candidate for the presidency which could have potentially weakened the Duterte support base for Marcos. In short, a voter who trusts President Duterte is also more likely to vote for a team that includes the president’s daughter, Mayor Sara, a natural successor and surrogate for a preferred Duterte legacy. A clear indicator of this trust and voter preference affinity was seen in the significant increase in survey ratings for Marcos, Jr. when Mayor Sara decided to be her vice-president, shifting much of her earlier electoral support base for the presidency to Marcos, Jr., especially in Mindanao. A CenPEG (Center for People Empowerment in Governance) correlational and regression test of the actual votes received by Marcos, Jr., and Mayor Sara shows a very high significant positive relationship which means that a vote for Marcos, Jr. almost always translates also to a vote for Duterte and vice-versa.

Disinformation Campaign and Political Narratives

As early as 2014, the Marcos family reportedly had an arrangement with the now defunct British political consulting firm Cambridge Analytica to rebrand the family image and revise the narratives of the Marcos dictatorship era in preparation for the national candidacy of Marcos, Jr. Social media platforms, especially Facebook and later TikTok became the main conduits for this rebranding campaign to put the Marcoses in a good light and push their major political rivals, especially Robredo, on the defensive through systematic disinformation campaigns. In consonance with this rebranding and disinformation campaign, the Marcos camp crafted a political message built around restoring an alleged golden era during the martial law years and moving forward through a “Unity Team” led by Marcos, Jr. and Mayor Sara Duterte. Consistent with this campaign strategy, Marcos, Jr. deliberately avoided public debates and fora to shield him from the inconvenient questions about his unimpressive personal and government track record and sought to project, instead, an inclusive personality relatable to many.

It appears from the election results that most voters embraced much of the Marcos rebranding and disinformation messages or remained unmoved by critics who sought to fact-check these false claims. Part of the explanation lies in the generational gap between the older voters who directly experienced the hardships under the dictatorship and the younger generation (40 years and below) who did not have those life-defining engagements with martial rule and are thus more vulnerable to historical revisionist accounts.

But perhaps a deeper explanation lies in the perception of many that the challenging times required a continuity agenda rather than a new change in leadership as shown in the unusually high trust ratings enjoyed by President Duterte. Thus, in the context of an extraordinary crisis such as the illegal drugs problem and the Covid-19 pandemic, it also appears that many voters were willing to provide more slack to the harsh and fatal excesses of authoritarianism displayed by Duterte. Radiating a sharply different inclusive persona and leadership style, Robredo’s campaign largely resonated with the educated middle classes, students, and professionals but apparently failed to change the views of the considerable number of Duterte supporters, mostly from the disadvantaged social classes and families. Ever in search of a strong and decisive savior-leader who will address their social and economic woes and political marginalization, these voters opted, once again, to test the promises and limits of the presidential team most closely linked to the country’s authoritarian political tradition.

Organizational and Financial Resources

Another extraordinary feature of the May 2022 election was the support given by the country’s most powerful and influential political families and oligarchs to the Marcos, Jr. - Duterte team. Among the most prominent of these families are those of former president Gloria Macapagal Arroyo who was a key orchestrator of the Marcos, Jr.– Duterte team, the Villars, Estradas, Floirendo-Lagdameos, Singsons, and the Romualdezes. The breakdown of the opposition Liberal Party since the 2016 election magnified this Marcos-Duterte advantage and Robredo lost an important organizational resource base that helped her win the vice presidency in 2016. Lacking this asset on the ground, the Robredo campaign depended largely on a movement of determined and passionate volunteer campaigners working with limited resources and with little or no previous experience in political campaigning. Robredo also received several endorsements from former government officials and some local politicians but the former had limited political reach and influence after retirement and the latter was more focused on attending to their own election concerns.

As partially indicated in their reported expenditures, candidates running for a national office require billions of pesos to run a serious campaign. Compiling data from Nielsen Ad Intel which tracks expenditures on media ads, the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) reports that at least P20 billion pesos were already spent by candidates for political ads on mainstream media (TV, radio, print, and billboards but excluding social media expenses) for the period from January 2021 to the end of March 2022. Among the senatorial candidates, the biggest spenders for this period were Mark Villar - 2.20 billion, Joel Villanueva – 2.05 billion, Sherwin Gatchalian and Alan Peter Cayetano - 1.55 billion, and Loren Legarda – 1.11 billion. The five other winning senatorial candidates in the May election (Miguel Zubiri, Jinggoy Estrada, JV Ejercito, Risa Hontiveros, and Chiz Escudero) also spent an average of P538 million on political ads on mainstream media alone for this period, not counting the two months before the May 9 election day.

For this same period, the following presidential candidates had the following expenses: Marcos, Jr. – 1.4 billion pesos, Robredo – 1.4 billion, Lacson – 1.20 billion, and Isko Moreno –1.19 billion. If the expenditures reported in Marcos, Jr.’s SOCE are added to his earlier expenses, he would have spent at least P2.02 billion, a conservative estimate since there are other expenses that are difficult to track including social media costs, influencer-celebrity fees, and financial largesse for political allies and local government officials including resources for vote-buying. Indeed, while not necessarily decisive for presidential elections as shown by the defeat of far more moneyed politicians such as Eduardo Cojuangco, Jr. in 1992, Manny Villar in 2010, and Mar Roxas in 2016, the possession of huge financial resources is always a distinct asset, especially for candidates running for a national office.

The Comelec, Smartmatic, and the Automated Election System (AES)

First implemented on a nationwide scale in the 2010 national elections, the automated election system (AES) introduced by the Comelec with a foreign-owned provider, Smartmatic, has continued to ignite questions about the lack of verifiability of the election results as reported by the vote counting machines (VCMs). Many of these election-related problems are rooted in the lack of confidence in the Comelec’s performance as a constitutional body mandated to run elections and aggravated by the lack of accountability of the AES provider, Smartmatic. The Comelec’s technical dependence on Smartmatic in running the AES and the failure or inadequacy of the safety mechanisms and auditing protocols provided by law to oversee the AES has resulted in a system whose contested results cannot be validated or confirmed conclusively, short of the actual count of the paper ballots.

In the May 2022 national elections, many of the problems that have hounded the AES surfaced once again, casting doubts on the veracity and accuracy of the results. The first set of problems focuses on the institutional structure and organizational competence of the Comelec related to its independence and professionalism as a constitutional body. For instance, the appointment by the president of the Comelec commissioners including its chairperson is not mediated by an initial process of public scrutiny of the appointees, at least something akin to the Judicial and Bar Council of the judiciary. Moreover, the Comelec has to attend to a quasi-judicial function of resolving electoral disputes and protests that detracts from its primary function of running a credible and accountable electoral process. Finally, the Comelec has failed to systematically develop its institutional competence to run the AES without depending on a foreign provider (Smartmatic) by ensuring that a critical mass of its own personnel including some of the commissioners to be knowledgeable about the AES.

As highlighted once again in the May 2022 elections, the safety and auditing mechanisms provided by the AES Law have been found to be wanting or not fully implemented. To start with, the source code (the human-readable version of a computer program) review process, as in past elections, has not been conclusively finished by local reviewers. The digital signatures required by law for members of the electoral boards and board of canvassers to authenticate transmitted electronic data were implemented partially in only three areas, Cebu City, Davao City, and some NCR cities. Moreover, there have been alarming reports that the secure digital cards (SDs) used in each vote counting machine (VCM) had been compromised because of the non-usage of the WORM format (write-once-read-many) in many precincts. Earlier, a close business crony of President Duterte, Dennis Uy of Davao City won the contract to deliver the VCMs and SD cards to each precinct all over the country, raising issues of propriety and conflicts of interest.

The other safeguards in the existing Automated Election Law, notably the Random Manual Audit (RAM), the Voter-Verified Paper Audit Trail (VVPAT), and the count review done by the Parish Pastoral Council for Responsible Voting (PPCRV) all fall short of ensuring the verifiability of election results. For instance, the RAM that includes one precinct per congressional district is a case of a “too little, too late” auditing protocol, usually finished when the national candidates had already been proclaimed. Made available for the visual inspection of each voter, the VVPAT only confirms the veracity of a voter’s final choice of candidates but does not figure in the process of verifying the machine-generated precinct count. The PPCRV counting review process compares the machine-generated precinct election returns with the printed and transmitted election returns it receives but does not verify the accuracy and authenticity of the precinct machine counts themselves. In short, questions about the accuracy and authenticity of machine-generated vote counts, if challenged, can only be conclusively resolved by the manual count of the paper ballots in each clustered precinct to be observed by representatives from the political parties and concerned citizens’ groups.

In light of these endemic problems with the AES, many concerned civil society groups, election watchdogs, and even some legislators have called for a system that ensures secret manual voting and public counting to be aided by computers and projectors in each precinct. Under this proposed alternative the transmission and canvassing of the votes will still be done electronically. The proposal is now called the Hybrid Election System (HES). Some bills were filed in the 18th Congress adopting the provisions of the HES with variations including a proposal to livestream the vote count which can be used as evidence in an electoral protest.

The adoption of an alternative verifiable and accountable election system (such as the HES) can be part of a body of political and electoral reforms, including measures to minimize if not eliminate voters’ vulnerability to various kinds of intimidation including vote-buying and disinformation; regulating and weakening the control of political dynasties over our political-electoral process; developing strong, programmatic political parties; and ensuring the independence and non-partisanship of the Comelec.

The State of the Opposition and Political Alignments

In Philippine politics, the political opposition is a loose term to refer broadly to personalities and parties that are out of power and seek to challenge and replace the incumbent elected leaders during designated election cycles. In the absence of cohesive and programmatic political parties that can consistently present an alternative platform, the so-called opposition is constructed every election cycle from the opportunistic, tactical alliances of competing political families and their leading personalities. An exception to this unending cycle of opportunistic, transactional politics has been the electoral engagement of legal Left parties. However, these progressive, people-oriented Left parties have yet to achieve a critical national electoral base to make their presence in legislative bodies and policy-making circles more viable.

In the May 2022 election, the broad political opposition against the Marcos, Jr.–Duterte alliance was divided into at least four major factions led by presidential bets Robredo, Isko Moreno, Lacson, and Pacquiao. The Left parties were represented by two major formations with the bigger party, the Makabayan bloc officially supporting Robredo, and the smaller one, Partido Lakas ng Masa, putting up its own presidential candidate, the trade union leader, Leody de Guzman. Partly because of these internal divisions and differences, the broad opposition failed to mount a more focused challenge against the administration team and suffered a major electoral defeat in 2022. Within the opposition bloc, the new forces that were inspired by Robredo who also tried to distance herself from the old Liberal Party, show some promise of reconstituting themselves into two possible formations. The first option is to operate as a broad NGO-type movement to help address the concrete socio-economic needs of disadvantaged families and communities. The second possibility is to operate as a political movement that eventually transforms into a new political party to contest elections. These are not mutually exclusive options but the lines of engagement will depend largely on the initiative and decision of Robredo as the preeminent leader of the movement. While this extraordinary role by Robredo is essential in the early stages, it has to be complemented and even supplanted later by a programmatic base of unity and action.

No stranger to direct electoral engagements particularly since the resumption of elections in 1987, the Left parties continue to face severe structural constraints provoked by radical changes in the political economy of globalized capitalism such as flexible work contracts (ENDO) that have weakened working class organizing and solidarity. Moreover, these parties continue to face systematic harassment of their political and organizing efforts seen as threats to long-established elite dominance. In particular, the Makabayan bloc has faced existential dangers to their individual and group political participation in the public sphere which is a major factor in the failure of Bayan Muna to win any seat in the House of Representatives in this year’s election. In light of the setbacks suffered in the May 2022 elections, the Left parties need to address at least two key concerns: working for a unified Left formation to contest elections and related political activities, and strengthening their distinct political identity while forging effective alliances with political allies.

Supporters of the Marcos, Jr.-Duterte team view its significant majority electoral support as a stable base of political unity for the whole country and the anchor for effective policy-making and implementation. However, the election has also given birth to a significant minority suspicious of the integrity of the recently concluded election process and primed to be more vigilant and critical of policies not aligned with good governance practices. In the context of policy-making and implementation, a “super-majority” in both houses of Congress is no guarantee of success because much of the transactions within Congress and with the presidency are highly opportunistic and volatile, especially in the absence of strong parties that could command commitment to strategic governance goals. Moreover, the absence of a bureaucracy properly insulated from highly partisan politics is another factor largely independent of so-called “super-majority” dynamics. Another constant driver of disunity and instability in government lies in the strategic rivalry among the most powerful political families as they compete for choice positions and privileges and prepare for the next election cycle. These competing interests by rival clans are bound to surface and impact governance as “super-majorities” in the country’s political system are in fact loose numerical groupings ever vulnerable to challenges both from within and outside the formal arenas of governance.

Challenges for the New Administration

The new administration of Marcos, Jr. and Sara Duterte faces a daunting set of governance challenges rooted in festering structural and institutional constraints amidst the Covid-19 pandemic and rapid changes in the regional and global environment. Successful governance outcomes typically require a confluence of effective and accountable leadership, adequate state capacity in implementing key policies, and social cohesion and unity.

An immediate focus on governance springs from the harsh reality that the Covid-19 crisis has impacted the entire range of interconnected day-to-day problems of economic recovery to health, education, the environment, and public order and security, just to mention the most pressing concerns. In response to these problems, will the new leadership continue the harsh authoritarian governance style of President Duterte in the belief that its significant majority electoral support is an endorsement of these practices? To do this, however, risks alienating the equally significant minority that did not vote for Marcos, Jr. (close to 22 million votes if all the non-Marcos votes are included) and also undermines the call for unity by the elected presidential team. Continuing the authoritarianism of the outgoing leadership also ignores the fact that many of its promised ambitious goals especially the elimination of illegal drugs and corruption ended up as failures and worsened the impunity of abusive officials.

An effective governance response to the overall crisis will also require the significant use of government resources to strengthen public institutions, especially in the health, education, and social welfare sectors that proved to be the most vulnerable during the emergency and most wanting of sustained support. Since these are the sectors imbued with much public interest, the new administration needs to be creative in finding new ways to raise much-needed revenues beyond simply incurring more debts or imposing new taxes.

Another critical area of reform that requires close attention is the strengthening of most government institutions to improve their professionalism and independence from political pressures and capacity to implement policies. The findings of the Commission on Audit (COA) on the poor capacity of many government agencies to use efficiently their budget allocations are an important reference point in this regard.

In the context of the new leadership’s call for unity, there are many pressing issues whose resolution could give credence to this claim. A resumption of the peace process with the armed guerrilla forces for a negotiated political settlement is one such agenda. This initiative will put an end to the costly and deadly militarist policies of the NTF-ELCAC which have only led to the systematic disregard of the people’s basic human rights and civil liberties. The new administration must also deal with the numerous documented cases of killings in the context of the drug war, especially in light of the suspended investigation of these cases by the International Criminal Court (ICC).

Amidst the many uncertainties of the regional and global environment, the new administration also needs to flesh out a foreign policy that protects and enhances our national interest while being supportive of international initiatives to address common concerns on health, climate change, and international peace and security. Cognizant of the increasing geopolitical tensions and conflict, the new leadership must also be careful of entangling alliances with any of the major powers while strengthening our ties with our neighbors in the region. #

Posted by CenPEG.org

22 June 2022

The May 2022 Elections and the Marcos Restoration: Looking Back and Beyond

In the country’s post-EDSA political history since 1986, the May 2022 election marks the first time the two most powerful political families running as a team won the presidency and vice-presidency with majority votes. Stunningly, the Marcos family is once again on top of the country’s political establishment with the proclamation by Congress of Ferdinand R. Marcos, Jr. as the 17th president of the republic. With Davao City Mayor Sara Duterte as the vice-president, the incoming administration led by Marcos, Jr., is set to define the country’s line of march in what may prove to be the most challenging circumstances in the country’s recent history.

Ousted from power and forced to go into exile after a combined military mutiny and peoples’ uprising in February 1986, the Marcos family systematically plotted a political restoration after being allowed back into the country in 1991, ironically to face corruption charges. As early as 1992, the family jump-started a political comeback with the former first lady, Imelda R. Marcos, running for the presidency, and Ferdinand R. Marcos, Jr. for the governorship of Ilocos Norte, the family’s political fiefdom. Mrs. Marcos lost her presidential bid, receiving a little over 10% of the votes but Marcos, Jr. easily won as governor.

It is instructive to note that in the early 1990s, the broad pro-Marcos national electoral base remained at almost 30%. This figure reflects the combined votes of Imelda Marcos and Eduardo Cojuangco, Jr., the close Marcos crony and oligarch who also ran a losing bid for the presidency in 1992, receiving about 18% of the votes. Looking back, the Marcos bloc could have won the presidency as early as 1992 had Mrs. Marcos and Cojuangco, Jr. joined forces, with their combined total votes of 29% edging out the 24% votes received by President Fidel V. Ramos, supported by outgoing president Corazon C. Aquino.

In retrospect, it also appears that the national electoral base of the Marcoses at about 30% proved to be a reliable resource for their succeeding bids for national positions. In his successful run for the Senate in 2010, Marcos, Jr. received almost 35% of the votes while in his failed bid for the vice presidency in 2016, he got more than 34%. Following this voting trend, Marcos, Jr.’s sister, Maria Imelda “Imee” Marcos also received, about 34% of the votes in her winning bid for the Senate in 2019.

The Presidential and Vice-Presidential Contest: A Victory Foretold?

There exists an uncanny consistency between the pre-election survey results and the final canvassed counts as reported by the Commission on Elections (Comelec). While some election watchdogs and opposition groups continue to cast doubt on the integrity of the automated election system, the unprecedented election results favoring the Marcos-Duterte team require some explanation backed up by some empirical validity or analytic plausibility.

A confluence of different factors helps untangle the events that shaped the final outcome. First, there exists the continuing reality of election bailiwicks rooted in regional-linguistic identities and loyalties as a critical resource base for national candidates. Second, the impact of President Duterte’s position on the campaign especially in light of his continued high survey ratings till the end of his term needs to be evaluated. Third, the extent to which the systematic campaign of disinformation and historical revisionism, especially in social media, impacted voter behavior also needs explanation. Closely related to this factor is the puzzle of why the political narrative and messaging of the Marcoses seemed to have resonated far better with the majority of the voters, especially with the poorer and disadvantaged social classes. Fourth, is the impact of the divided opposition on the campaign and voter choices. Fifth, the overall effect of the huge financial and organizational resources of the Marcos-Duterte team especially with the support of other powerful families and oligarchs, and various local government officials. A final factor requires an examination of the continuing problems and impact of an automated electoral system (AES), especially under the management of a Commission on Elections (Comelec) and a foreign service provider (Smartmatic) whose past and current records have not inspired trust and confidence in the system.

The Regional Distribution of Votes and Election Bailiwicks

Without addressing for now the many questions raised on the credibility and verifiability of the election returns generated by the vote counting machines and as reported by the Comelec, what can be inferred from the official election results? (See Table 1)

Table 1: Election Returns as Reported by the Commission on Elections (COMELEC) Transparency Server as of 13 May 2022 and provided by the National Movement for Free Elections (NAMFREL). Processed by Dr. Felix P. Muga, CenPEG Senior Research Fellow.

On 26 May 2022, Congress acting as the National Board of Canvassers proclaimed former senator Ferdinand R. Marcos, Jr., and Mayor Sara Duterte as the new president and vice-president. With 98.84% or 171 out of 173 of the certificates of the canvas (CoCs) counted, Marcos, Jr. received 31,629,783 votes or 58.77% of the votes counted while Duterte received 32,208,417 or 61.33%. Presidential candidate Vice-President Robredo trailed far behind with 15,035,773 votes (27.94% of votes counted) and her running mate, Senator Francisco Pangilinan had 9,329,207 votes (17.82%).

In comparison with the 2016 vice-presidential contest which also featured Robredo and Marcos, Jr. as the top two candidates, the 2022 presidential contest between them as the leading bets showed a sharp reversal of results. In 2016, Robredo won over Marcos, Jr., by a narrow margin of 278,566 votes after a recount in some contested precincts in a final decision by the Supreme Court in response to an election protest filed by losing candidate Marcos, Jr. In the vice-presidential race in 2016, Robredo won in nine of the regions while Marcos, Jr. prevailed in the other nine, including the CAR, NCR, and the Overseas Absentee Voters.

In the 2022 presidential contest, Robredo won in only two regions, her home region, (Bicol-Region 5), and Region 6 (Iloilo, Capiz, Aklan, Antique, Negros Occidental, and Guimaras), a traditional Liberal Party and an opposition stronghold. On full display in the May 2022 election was the continuing potency of regional bailiwick votes but lopsidedly in favor of the Marcos-Duterte team. In the Ilocano heartland of Regions 1 and 2, Marcos, Jr. enjoyed a huge lead of 3.66 million votes over Robredo, equivalent to an 82% share of the total votes in both regions while the latter received only about 9.5% of the total votes. Showing the same loyalty to a homegrown candidate, the Bicol region also gave Robredo a 1.88 million vote edge over Marcos, Jr. and received a 73% share of the region’s total votes. However, Marcos Jr. still managed to get a 17% share of the Bicolano votes, bigger than the 10% vote share of Robredo in the two Ilocano bailiwicks of Regions 1 and 2.

Predictably, Marcos, Jr. also won handily in the Duterte bailiwick of the Davao provinces (Region 11), with a winning margin of 1.93 million votes over Robredo or a 79% share of the total regional votes. Pacquiao had more votes than Robredo in Region 11, getting an 8% share of the total (202,581) to the latter’s 5% (134,658). Pacquiao also placed second to Marcos, Jr. in Regions 10 and 12, getting more votes than Robredo in these Mindanao areas.

Unlike in the 2016 elections when Robredo won over Marcos in four regions in Mindanao (ARMM, Regions 9, 10, and 13), she ended up losing in all of the Mindanao regions in 2022. Robredo’s big loss in what is now the Bangsa Moro Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) was also surprising since she beat Marcos, Jr. by a wide margin here in 2016 (44% vs. 27%). This region suffered the worst atrocities during the Marcos dictatorship and the common view lingered that this would work against Marcos, Jr. While some of the powerful local clans supported Marcos, Jr., notably the Tans of Sulu and a faction of the divided Mangudadatu families, Robredo also managed to get the endorsement of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), one faction of the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), and the Hatamans of Basilan. However, the Duterte factor, especially in light of the Marcos-Sara Duterte team-up is the new element that was not prominent in the Robredo-Marcos, Jr., faceoff in the 2016 election. In 2022, Marcos, Jr. turned the tables against Robredo by winning 55% of the BARMM votes against Robredo’s 24%.

The voting results in the National Capital Region (NCR) are also instructive in terms of the seeming contradictions and unexpected outcomes. The NCR has the largest concentration of the country’s most affluent families and educated middle classes. Compared with the other regions the NCR has also the easiest access and most exposure to all kinds of media including the various social media platforms. It is the country’s business and financial center and also hosts the most heterogeneous demographic mix of individuals coming from all parts of the country. Traditionally an opposition political center, the NCR, in fact, surprised many with the victory of Marcos, Jr. in the 2016 election where he received 46% of the votes against Robredo’s 28%. With the entry of Manila Mayor Francisco Domagoso “Isko Moreno” in the presidential race in 2022, many expected the election in the NCR to be more competitive. But once again, Marcos, Jr. prevailed in both the NCR and the city of Manila where Isko Moreno managed to win only in his Manila congressional district. For the whole of the NCR, Marcos, Jr. received 55% of the votes against Robredo’s 30% while Moreno struggled with only 9% of the votes. Moreover, Marcos, Jr. also won in all of the 16 cities of the NCR and in the municipality of Pateros. In the two cities in the NCR with the biggest number of votes, Quezon City and Manila, Marcos, Jr. also led by huge margins over Robredo. In Quezon City, Marcos Jr. received 57% of the votes against Robredo’s 34% while in the city of Manila, the former got 40% of the votes compared with Robredo’s, 22%. Mayor Isko Moreno placed second to Marcos, Jr. in Manila with 34% of the votes.

For the election contest at the provincial level, Robredo won in only 15 out of the country’s 81 provinces. Of these 15 provinces, six belong to her home region (Region 5- Albay, Camarines Norte, Camarines Sur, Catanduanes, Masbate, and Sorsogon) and five provinces to a Liberal Party and opposition regional stronghold (Region 6- Aklan, Antique, Capiz, Iloilo, and Negros Occidental). The remaining three provinces that provided Robredo with winning margins included Rizal, Quirino, and Biliran. Robredo won in three of the top 10 vote-rich provinces, (Negros Occidental, Iloilo, and Rizal) but only by an average winning margin over Marcos, Jr. of 140,000 votes. In contrast, Marcos, Jr. posted an average winning margin of 608,000 votes over Robredo in the seven other top-10 vote-rich provinces (Cebu, Cavite, Pangasinan Laguna, Bulacan Batangas, and Pampanga). For instance, in these seven provinces, Marcos, Jr. led Robredo by the following huge margins of victory: Pangasinan, 1.12 million votes; Cebu, 897,313; Bulacan, 643,894; Cavite, 479,154; Laguna, 418,862; Batangas, 381,431; and Pampanga, 310,863.

What seems incredulous about the final Comelec results is that Robredo is shown to have added only 601,863 thousand votes to her 2016 total or a measly 4% increase. In contrast, Marcos, Jr. added 17,489,532 million to his 2016 votes or an increase of 124%!

Explaining the Marcos, Jr.-Sara Duterte Electoral Victory

Long supported by historical data on electoral behavior in the country, the regional-linguistic ties of candidates with voters as seen in voting bailiwicks continue to be a critical factor in voter preferences. In the 2022 presidential elections, these regional bailiwicks proved to be formidable factors once again as shown in the initial advantage enjoyed by Marcos, Jr. and Sara Duterte with the melding of their voting strongholds, the so-called “solid North and solid South” votes. Comparing the voting strength of their tested regional bailiwicks (Regions 1 and 2 for Marcos plus Region 11 of the Dutertes vs. Regions 5 and 6 for Robredo), Marcos, Jr. immediately gained a 1.8 million advantage over vice-president Robredo. But the key question lies in explaining why the Marcos-Duterte team also dominated in all of the regions outside of the two regional bailiwicks won by Robredo since bailiwick votes alone cannot explain the final outcome except in closely contested elections.

High Trust Ratings for President Duterte and Election Impact

A confluence of a number of factors contributed to defining the final election verdict. The continuing high trust and performance ratings of President Duterte up to the end of his term impacted voter preferences. As shown by the country’s electoral record since 1986, a presidential candidate endorsed by or closely associated with the outgoing president with low trust and performance ratings usually ended up losing the election. The only exception to this trend appears to be the victory of the Aquino administration-backed Fidel V. Ramos in the 1992 election in a closely contested match marred by allegations of massive fraud and vote-buying. Unlike his predecessors who all ended their terms with low trust ratings below 50% (as low as 10% for Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo), President Duterte sets a precedent with an average high trust rating of not less than 70% for his six years in office. As shown by all credible public opinion survey groups, Duterte maintained these high ratings even during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic. Even the allegations of coddling close allies charged with massive corruption (Pharmally scandal), and the red-tagging of opposition groups and personalities did not dent his high trust ratings. In terms of voter preferences, the high trust ratings given to the outgoing president apparently translated to electoral support for the team (Marcos, Jr.-Sara Duterte) perceived to be most closely aligned with the persona and policies of the outgoing president and administration.

While Mr. Duterte openly expressed his misgivings about the candidacy of Marcos, Jr., calling him a “weak leader” with no significant achievements, he did not also endorse an alternative candidate for the presidency which could have potentially weakened the Duterte support base for Marcos. In short, a voter who trusts President Duterte is also more likely to vote for a team that includes the president’s daughter, Mayor Sara, a natural successor and surrogate for a preferred Duterte legacy. A clear indicator of this trust and voter preference affinity was seen in the significant increase in survey ratings for Marcos, Jr. when Mayor Sara decided to be her vice-president, shifting much of her earlier electoral support base for the presidency to Marcos, Jr., especially in Mindanao. A CenPEG (Center for People Empowerment in Governance) correlational and regression test of the actual votes received by Marcos, Jr., and Mayor Sara shows a very high significant positive relationship which means that a vote for Marcos, Jr. almost always translates also to a vote for Duterte and vice-versa.

Disinformation Campaign and Political Narratives

As early as 2014, the Marcos family reportedly had an arrangement with the now defunct British political consulting firm Cambridge Analytica to rebrand the family image and revise the narratives of the Marcos dictatorship era in preparation for the national candidacy of Marcos, Jr. Social media platforms, especially Facebook and later TikTok became the main conduits for this rebranding campaign to put the Marcoses in a good light and push their major political rivals, especially Robredo, on the defensive through systematic disinformation campaigns. In consonance with this rebranding and disinformation campaign, the Marcos camp crafted a political message built around restoring an alleged golden era during the martial law years and moving forward through a “Unity Team” led by Marcos, Jr. and Mayor Sara Duterte. Consistent with this campaign strategy, Marcos, Jr. deliberately avoided public debates and fora to shield him from the inconvenient questions about his unimpressive personal and government track record and sought to project, instead, an inclusive personality relatable to many.

It appears from the election results that most voters embraced much of the Marcos rebranding and disinformation messages or remained unmoved by critics who sought to fact-check these false claims. Part of the explanation lies in the generational gap between the older voters who directly experienced the hardships under the dictatorship and the younger generation (40 years and below) who did not have those life-defining engagements with martial rule and are thus more vulnerable to historical revisionist accounts.

But perhaps a deeper explanation lies in the perception of many that the challenging times required a continuity agenda rather than a new change in leadership as shown in the unusually high trust ratings enjoyed by President Duterte. Thus, in the context of an extraordinary crisis such as the illegal drugs problem and the Covid-19 pandemic, it also appears that many voters were willing to provide more slack to the harsh and fatal excesses of authoritarianism displayed by Duterte. Radiating a sharply different inclusive persona and leadership style, Robredo’s campaign largely resonated with the educated middle classes, students, and professionals but apparently failed to change the views of the considerable number of Duterte supporters, mostly from the disadvantaged social classes and families. Ever in search of a strong and decisive savior-leader who will address their social and economic woes and political marginalization, these voters opted, once again, to test the promises and limits of the presidential team most closely linked to the country’s authoritarian political tradition.

Organizational and Financial Resources

Another extraordinary feature of the May 2022 election was the support given by the country’s most powerful and influential political families and oligarchs to the Marcos, Jr. - Duterte team. Among the most prominent of these families are those of former president Gloria Macapagal Arroyo who was a key orchestrator of the Marcos, Jr.– Duterte team, the Villars, Estradas, Floirendo-Lagdameos, Singsons, and the Romualdezes. The breakdown of the opposition Liberal Party since the 2016 election magnified this Marcos-Duterte advantage and Robredo lost an important organizational resource base that helped her win the vice presidency in 2016. Lacking this asset on the ground, the Robredo campaign depended largely on a movement of determined and passionate volunteer campaigners working with limited resources and with little or no previous experience in political campaigning. Robredo also received several endorsements from former government officials and some local politicians but the former had limited political reach and influence after retirement and the latter was more focused on attending to their own election concerns.

As partially indicated in their reported expenditures, candidates running for a national office require billions of pesos to run a serious campaign. Compiling data from Nielsen Ad Intel which tracks expenditures on media ads, the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) reports that at least P20 billion pesos were already spent by candidates for political ads on mainstream media (TV, radio, print, and billboards but excluding social media expenses) for the period from January 2021 to the end of March 2022. Among the senatorial candidates, the biggest spenders for this period were Mark Villar - 2.20 billion, Joel Villanueva – 2.05 billion, Sherwin Gatchalian and Alan Peter Cayetano - 1.55 billion, and Loren Legarda – 1.11 billion. The five other winning senatorial candidates in the May election (Miguel Zubiri, Jinggoy Estrada, JV Ejercito, Risa Hontiveros, and Chiz Escudero) also spent an average of P538 million on political ads on mainstream media alone for this period, not counting the two months before the May 9 election day.

For this same period, the following presidential candidates had the following expenses: Marcos, Jr. – 1.4 billion pesos, Robredo – 1.4 billion, Lacson – 1.20 billion, and Isko Moreno –1.19 billion. If the expenditures reported in Marcos, Jr.’s SOCE are added to his earlier expenses, he would have spent at least P2.02 billion, a conservative estimate since there are other expenses that are difficult to track including social media costs, influencer-celebrity fees, and financial largesse for political allies and local government officials including resources for vote-buying. Indeed, while not necessarily decisive for presidential elections as shown by the defeat of far more moneyed politicians such as Eduardo Cojuangco, Jr. in 1992, Manny Villar in 2010, and Mar Roxas in 2016, the possession of huge financial resources is always a distinct asset, especially for candidates running for a national office.

The Comelec, Smartmatic, and the Automated Election System (AES)

First implemented on a nationwide scale in the 2010 national elections, the automated election system (AES) introduced by the Comelec with a foreign-owned provider, Smartmatic, has continued to ignite questions about the lack of verifiability of the election results as reported by the vote counting machines (VCMs). Many of these election-related problems are rooted in the lack of confidence in the Comelec’s performance as a constitutional body mandated to run elections and aggravated by the lack of accountability of the AES provider, Smartmatic. The Comelec’s technical dependence on Smartmatic in running the AES and the failure or inadequacy of the safety mechanisms and auditing protocols provided by law to oversee the AES has resulted in a system whose contested results cannot be validated or confirmed conclusively, short of the actual count of the paper ballots.

In the May 2022 national elections, many of the problems that have hounded the AES surfaced once again, casting doubts on the veracity and accuracy of the results. The first set of problems focuses on the institutional structure and organizational competence of the Comelec related to its independence and professionalism as a constitutional body. For instance, the appointment by the president of the Comelec commissioners including its chairperson is not mediated by an initial process of public scrutiny of the appointees, at least something akin to the Judicial and Bar Council of the judiciary. Moreover, the Comelec has to attend to a quasi-judicial function of resolving electoral disputes and protests that detracts from its primary function of running a credible and accountable electoral process. Finally, the Comelec has failed to systematically develop its institutional competence to run the AES without depending on a foreign provider (Smartmatic) by ensuring that a critical mass of its own personnel including some of the commissioners to be knowledgeable about the AES.

As highlighted once again in the May 2022 elections, the safety and auditing mechanisms provided by the AES Law have been found to be wanting or not fully implemented. To start with, the source code (the human-readable version of a computer program) review process, as in past elections, has not been conclusively finished by local reviewers. The digital signatures required by law for members of the electoral boards and board of canvassers to authenticate transmitted electronic data were implemented partially in only three areas, Cebu City, Davao City, and some NCR cities. Moreover, there have been alarming reports that the secure digital cards (SDs) used in each vote counting machine (VCM) had been compromised because of the non-usage of the WORM format (write-once-read-many) in many precincts. Earlier, a close business crony of President Duterte, Dennis Uy of Davao City won the contract to deliver the VCMs and SD cards to each precinct all over the country, raising issues of propriety and conflicts of interest.

The other safeguards in the existing Automated Election Law, notably the Random Manual Audit (RAM), the Voter-Verified Paper Audit Trail (VVPAT), and the count review done by the Parish Pastoral Council for Responsible Voting (PPCRV) all fall short of ensuring the verifiability of election results. For instance, the RAM that includes one precinct per congressional district is a case of a “too little, too late” auditing protocol, usually finished when the national candidates had already been proclaimed. Made available for the visual inspection of each voter, the VVPAT only confirms the veracity of a voter’s final choice of candidates but does not figure in the process of verifying the machine-generated precinct count. The PPCRV counting review process compares the machine-generated precinct election returns with the printed and transmitted election returns it receives but does not verify the accuracy and authenticity of the precinct machine counts themselves. In short, questions about the accuracy and authenticity of machine-generated vote counts, if challenged, can only be conclusively resolved by the manual count of the paper ballots in each clustered precinct to be observed by representatives from the political parties and concerned citizens’ groups.

In light of these endemic problems with the AES, many concerned civil society groups, election watchdogs, and even some legislators have called for a system that ensures secret manual voting and public counting to be aided by computers and projectors in each precinct. Under this proposed alternative the transmission and canvassing of the votes will still be done electronically. The proposal is now called the Hybrid Election System (HES). Some bills were filed in the 18th Congress adopting the provisions of the HES with variations including a proposal to livestream the vote count which can be used as evidence in an electoral protest.

The adoption of an alternative verifiable and accountable election system (such as the HES) can be part of a body of political and electoral reforms, including measures to minimize if not eliminate voters’ vulnerability to various kinds of intimidation including vote-buying and disinformation; regulating and weakening the control of political dynasties over our political-electoral process; developing strong, programmatic political parties; and ensuring the independence and non-partisanship of the Comelec.

The State of the Opposition and Political Alignments

In Philippine politics, the political opposition is a loose term to refer broadly to personalities and parties that are out of power and seek to challenge and replace the incumbent elected leaders during designated election cycles. In the absence of cohesive and programmatic political parties that can consistently present an alternative platform, the so-called opposition is constructed every election cycle from the opportunistic, tactical alliances of competing political families and their leading personalities. An exception to this unending cycle of opportunistic, transactional politics has been the electoral engagement of legal Left parties. However, these progressive, people-oriented Left parties have yet to achieve a critical national electoral base to make their presence in legislative bodies and policy-making circles more viable.

In the May 2022 election, the broad political opposition against the Marcos, Jr.–Duterte alliance was divided into at least four major factions led by presidential bets Robredo, Isko Moreno, Lacson, and Pacquiao. The Left parties were represented by two major formations with the bigger party, the Makabayan bloc officially supporting Robredo, and the smaller one, Partido Lakas ng Masa, putting up its own presidential candidate, the trade union leader, Leody de Guzman. Partly because of these internal divisions and differences, the broad opposition failed to mount a more focused challenge against the administration team and suffered a major electoral defeat in 2022. Within the opposition bloc, the new forces that were inspired by Robredo who also tried to distance herself from the old Liberal Party, show some promise of reconstituting themselves into two possible formations. The first option is to operate as a broad NGO-type movement to help address the concrete socio-economic needs of disadvantaged families and communities. The second possibility is to operate as a political movement that eventually transforms into a new political party to contest elections. These are not mutually exclusive options but the lines of engagement will depend largely on the initiative and decision of Robredo as the preeminent leader of the movement. While this extraordinary role by Robredo is essential in the early stages, it has to be complemented and even supplanted later by a programmatic base of unity and action.

No stranger to direct electoral engagements particularly since the resumption of elections in 1987, the Left parties continue to face severe structural constraints provoked by radical changes in the political economy of globalized capitalism such as flexible work contracts (ENDO) that have weakened working class organizing and solidarity. Moreover, these parties continue to face systematic harassment of their political and organizing efforts seen as threats to long-established elite dominance. In particular, the Makabayan bloc has faced existential dangers to their individual and group political participation in the public sphere which is a major factor in the failure of Bayan Muna to win any seat in the House of Representatives in this year’s election. In light of the setbacks suffered in the May 2022 elections, the Left parties need to address at least two key concerns: working for a unified Left formation to contest elections and related political activities, and strengthening their distinct political identity while forging effective alliances with political allies.

Supporters of the Marcos, Jr.-Duterte team view its significant majority electoral support as a stable base of political unity for the whole country and the anchor for effective policy-making and implementation. However, the election has also given birth to a significant minority suspicious of the integrity of the recently concluded election process and primed to be more vigilant and critical of policies not aligned with good governance practices. In the context of policy-making and implementation, a “super-majority” in both houses of Congress is no guarantee of success because much of the transactions within Congress and with the presidency are highly opportunistic and volatile, especially in the absence of strong parties that could command commitment to strategic governance goals. Moreover, the absence of a bureaucracy properly insulated from highly partisan politics is another factor largely independent of so-called “super-majority” dynamics. Another constant driver of disunity and instability in government lies in the strategic rivalry among the most powerful political families as they compete for choice positions and privileges and prepare for the next election cycle. These competing interests by rival clans are bound to surface and impact governance as “super-majorities” in the country’s political system are in fact loose numerical groupings ever vulnerable to challenges both from within and outside the formal arenas of governance.

Challenges for the New Administration

The new administration of Marcos, Jr. and Sara Duterte faces a daunting set of governance challenges rooted in festering structural and institutional constraints amidst the Covid-19 pandemic and rapid changes in the regional and global environment. Successful governance outcomes typically require a confluence of effective and accountable leadership, adequate state capacity in implementing key policies, and social cohesion and unity.

An immediate focus on governance springs from the harsh reality that the Covid-19 crisis has impacted the entire range of interconnected day-to-day problems of economic recovery to health, education, the environment, and public order and security, just to mention the most pressing concerns. In response to these problems, will the new leadership continue the harsh authoritarian governance style of President Duterte in the belief that its significant majority electoral support is an endorsement of these practices? To do this, however, risks alienating the equally significant minority that did not vote for Marcos, Jr. (close to 22 million votes if all the non-Marcos votes are included) and also undermines the call for unity by the elected presidential team. Continuing the authoritarianism of the outgoing leadership also ignores the fact that many of its promised ambitious goals especially the elimination of illegal drugs and corruption ended up as failures and worsened the impunity of abusive officials.

An effective governance response to the overall crisis will also require the significant use of government resources to strengthen public institutions, especially in the health, education, and social welfare sectors that proved to be the most vulnerable during the emergency and most wanting of sustained support. Since these are the sectors imbued with much public interest, the new administration needs to be creative in finding new ways to raise much-needed revenues beyond simply incurring more debts or imposing new taxes.

Another critical area of reform that requires close attention is the strengthening of most government institutions to improve their professionalism and independence from political pressures and capacity to implement policies. The findings of the Commission on Audit (COA) on the poor capacity of many government agencies to use efficiently their budget allocations are an important reference point in this regard.

In the context of the new leadership’s call for unity, there are many pressing issues whose resolution could give credence to this claim. A resumption of the peace process with the armed guerrilla forces for a negotiated political settlement is one such agenda. This initiative will put an end to the costly and deadly militarist policies of the NTF-ELCAC which have only led to the systematic disregard of the people’s basic human rights and civil liberties. The new administration must also deal with the numerous documented cases of killings in the context of the drug war, especially in light of the suspended investigation of these cases by the International Criminal Court (ICC).

Amidst the many uncertainties of the regional and global environment, the new administration also needs to flesh out a foreign policy that protects and enhances our national interest while being supportive of international initiatives to address common concerns on health, climate change, and international peace and security. Cognizant of the increasing geopolitical tensions and conflict, the new leadership must also be careful of entangling alliances with any of the major powers while strengthening our ties with our neighbors in the region. #

- The May 2022 Elections and the Marcos Restoration: Looking Back and Beyond

- Rethinking ASEAN ties with U.S., signs of another Cold War may be in the air

- A quest for peace in Europe

- Maelstrom Over the Killing Fields

- The Russians are coming!

- Disqualification cases roil Marcos camp; biggest Left political bloc backs Robredo-Pangilinan team

- A Race for Power of Political Dynasties

- On proclaiming a winning candidate

- CLASH OF POLITICAL DYNASTIES ACCENTS MAY 2022 ELECTIONS

- The Great Faith

- We need to renew 'new politics' for the May 2022 polls

- Major Presidential Bets Formalize Candidacies but Last-Minute Surprises still Possible till Mid-November

- The shadow of Bannon in Biden's anti-China strategy

- Biden's 'Pivot to Asia' at a dead end

- Is the US aching for a war with China over Taiwan?

- Dollars for America's war machine, human losses

- Learning from an awakened dragon

- War-torn Afghanistan’s future in the hands of the Taliban

- The formidable force to contend with in 2022 elections

- With Afghan debacle, will allies trust the US?

- The Ideal OQC Operations for The 2022 elections

- RACE FOR THE 2022 PRESIDENCY GAINS MOMENTUM

- UGNAYANG PANLABAS SA ILALIM NI DUTERTE: PANALO O TALO?

- Afghanistan, where war knows no end

- A President’s Death, an ICC Call, and Realignments ahead of the 2022 Elections: A Gathering Storm?

- Simplify transmission of election results for transparent 2022 elections

- Old ways must go in May 2022 polls

- Jostling for the presidency amid the pandemic and flaws in the election system

- Clean voters’ database: A challenge to a transparent 2022 elections

- REFLECTIONS ON WOMEN AND RACE DURING THE YEAR OF THE PANDEMIC

Center for People Empowewrment in Governance (CenPEG), Philippines. All rights reserved